You might expect that we were out of the house early for the ~18 hour drive from the Seattle area to Death Valley, but you'd be wrong. It was 8:00am when we pulled out of the driveway, and pointed the truck south towards our destination. Before long, the city gave way to open space, the golden glow in stark contrast to the cloudy skies we were leaving behind.

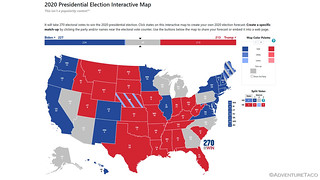

That wasn't all we were leaving behind - not by a long shot. It was Wednesday, November 4, 2020 - one day after a rather interesting election for our country. We'd purposefully scheduled the trip for this time - figuring there was no better way to deal with the situation than to disconnect ourselves from it for a few days. Obviously, we had no idea who would win - the map looked like this at the time:

For a while, we listened to the radio. When it was clear that this wasn't going to be the day for answers, we switched to podcasts. We drove. And drove. Through Washington, Oregon, a little bit of Idaho, and a lot of Nevada. Into the dark, and eventually into the next day. Excitement was not the name of the game, though there were a few minutes of adrenaline as I was pulled over just outside of Winnemucca for 63mph in a 35mph!  For the first time ever, I was let off with a warning - a good omen perhaps, for the rest of the trip?

For the first time ever, I was let off with a warning - a good omen perhaps, for the rest of the trip?

An honest mistake. And a lucky outcome.

Ultimately - at 2:45am - we reached Beatty, NV and found a spot above town to setup the tent. Sleep came quickly, a warm breeze welcoming us to the desert.

Onto the Trail

You might expect that after arriving at 2:45am, that we'd sleep in a bit before heading into Death Valley National Park, but you'd be wrong. I set my alarm for 5:30am - hoping to catch a colorful sunrise. With clear skies, I had no such luck - but we pulled ourselves out of bed anyway just after the sun came up, so we could spend most of the day exploring.

Camp less than a mile outside of Beatty, NV. A nice spot.

We made a quick pit stop to fill up on fuel and to grab a hat - @mrs.turbodb had forgotten hers - and then headed towards Death Valley and Sunlight Pass.

Continuing east on CA-190, we spent only enough time in Death Valley proper to snap a photo of Mesquite Dunes - a place I haven't visited, but can't wait to hike - before climbing over Towne Pass and into Panamint Valley.

We were getting close now, though even as we turned south onto Panamint Valley Road, there was asphalt under the tires.

Making our way south for 25 miles - to the northern tip of the Slate Mountains - we got our first taste of two very different sounds I associate with the desert. Jets. And burros.

The first of many. Exciting every time.

Local riff-raff.

By 10:00am, we'd reached our destination: the southern end - at least for our purposes - of the Nadeau Trail. Perched at the top of the Slate Mountains looking north into Panamint Valley, it was the perfect time and place for breakfast, as well as a bit of history about the road we were about to travel!

The Nadeau Trail is named after freighter Remi Nadeau, one of the many unsung heroes of the Death Valley days. Although seldom acknowledged, freighters played a vital role in the development of remote mining communities by providing economical transportation to haul out their ore and bring supplies on their way back. Nadeau moved west in 1860, and over the next 20 years, forged a successful freighting empire that eventually dominated the eastern California market. There is hardly a mine worth the name that didn't resound with the bells of his teams. Nadeau's teamsters hauled merchandise from LA to Salt Lake City and as far as Montana, freighted borax for Searles Valley, and silver for Darwin, Resting Springs, and Ivanpah. In 1875-1876 his teams made headlines freighting Panamint City's 400-pound silver ingots all the way across the desert to the railroad station at Mojave.

The Modoc Mine, in the Argus Range at the north end of Panamint Valley, was another of his successes. To reduce travel time, in the spring of 1877 he had a large crew of Chinese immigrants build the shortest possible access road to the Modoc Mine - which would later be named the Nadeau Trail. From the pass into Searles Valley the completed road went straight up Panamint Valley, hugging the Argus Range to shave precious miles, then cut west to the mine. It was indeed so straight that it earned the nickname of Shotgun Road. By the end of 1876, Nadeau had already delivered $400,000 worth of ingots to Mojave. Nadeau's fees were probably around $50 per ton, so that his road was paying back a tidy $500 a day - not to mention the extra cash he was picking up by hauling charcoal from Wildrose Canyon's kilns to the Modoc smelters. Hiking Western Death Valley

And with that, we were off, along the only twisty section of the trail as we descended Slate Pass - the rock retaining walls of Nadeau's Chinese laborers supporting us; the trail as straight as an arrow across the valley floor.

Soon, we reached the valley floor, entering the Water Canyon wash, the height of its walls adding a little perspective as to the amount of water that once flowed through these parts.

Here too, we crossed the Trona-Wildrose Road, where we were greeted not only with the Nadeau National Recreation Trail marker above, but also by a moniker that would be much more familiar over the coming days, given that the vast majority of this trail is technically outside of Death Valley National Park - the BLM's road designation: P105.

Only a few hundred yards north, the sight of old tailings on the lower slopes of the Argus Range caught our eye. I hadn't mapped a side trip at this point, but there's no better way to enjoy yourself than to play a trip like this by ear, so we turned west and soon found ourselves at the old Diatom Plus site - apparently a relatively recent mine from the mid-1980's.

The day - no, the trip - would continue this way. Short spurts along the Nadeau Trail - it is only 27 miles long, after all - broken up by journeys into the canyons and onto the ridges of the Argus Mountains.

The Reilly Townsite was the next detour to catch our eye - a rare sign along the Nadeau marking the path. Established in 1882, it once housed a 10-stamp mill, boarding house, general store, blacksmith shop, and post office. In all, over 32 buildings existed at the site, with more than 60 residents. Like many mines in the area, Reilly was ultimately a failure - over $200,000 was invested, and only $21,500 was recovered as silver bullion.

The water pump on the 10-stamp mill failed the first time it was run.

Only 45 minutes had elapsed, and we were already enjoying ourselves immensely - so much to see in such a concentrated area. Continuing north now, the straight shot was broken by numerous washes that made their way down the alluvial fans, none raising any sort of concern at this early stage.

Soon we found ourselves at the road leading to Shepherd Canyon. This was our first planned side trip, with two mines and a cabin marked on our route. The Onyx Mine was the first of these, a large concrete platform supporting three enormous concrete cutting tables, of its small gem-cutting factory.

Nestled within a couple bluffs just outside the canyon, this mine was worked on and off between 1925 and the 1950s, producing a few hundred tons of gemstone - drill holes and old mining equipment still littering the surrounding area.

The bearings on the cooling fan of this tractor were still so smooth that the light breeze was spinning the fan as we arrived.

We didn't spend long at the Onyx mine, as something deeper in the canyon was the real reason we'd turned west here - the Kopper King Mine. Because seriously, if you're ballsy enough to misspell what you're mining, it must be good - amiright?  And so, into the canyon we plunged.

And so, into the canyon we plunged.

Looking back, Shepherd Canyon and the Kopper King were a nice intro to the trip. They were - at the time - quite interesting, but in comparison to the rest of the trip, I'd have to say now that they were definitely not the most interesting from either a canyon or mine perspective.

@mrs.turbodb: What's in there?

Me: Let's find out.

Well then, hello azurite.

The Kopper King did however have a nicely maintained cabin - one that is clearly loved by its caretakers. If you find it, remember to respect the hard work that has gone into this place; desert cabins are easily ruined by careless visitors.

Starting back toward Panamint, and about halfway between the Kopper King and Onyx mines, a small side road leads down into Shepherd Canyon proper. While the road is washed out, a short hike meanders over the landscape - over dry falls, through springs, and past the dilapidated trailer of an old desert hermit - a lone palm tree providing invaluable shade in this arid climate.

A once-loved refuge.

Back toward the Nadeau Trail.

As we turned north to navigate the Nadeau, it was 2:30pm - only 2-3 more hours of daylight before we'd need to find somewhere to camp. It was an interesting predicament, given that I'd planned a 7.5 mile hike for the afternoon. But, as usual, I'm getting ahead of myself - this section of the trail was actually one of the more interesting, and despite our (my) desire to move quickly, we slowed down to take it all in.

Handiwork of the Chinese road builders, still standing strong in smaller washes that haven't seen water in decades.

Needle in the haystack that is Panamint Valley.

All day, we'd been treated to the road of F-18s flying through the valley. Each time we'd seen them, they'd been along the east side or several thousand feet above us, the roar of their engines still enough to get our blood flowing. And then, as we climbed an undulation in the alluvial fan, we finally got to see one a little closer.

F-18, nose number 218. Two seats. I'll take the front one, please.

A few minutes later, we ran into the most rutted wash we'd encounter on the Nadeau Trail. A 30" drop into the wash - and a similar climb out - a little interesting in the loose material, and right at the edge of what a 1st gen wheelbase could maneuver.

Soon after, we turned west one final time - today - and started up Knight Canyon. The longest and deepest canyon in the Argus Range Wilderness, and "one of the most exciting," according to Digonnet, it boasts three springs, a couple of old mine camps, and a dry fall! But as we pulled up at the gate that marked the end of the road and beginning of the hike, those were not what we were discussing.

Rather, we were discussing the time - it was 3:30pm. With sunset at 4:45pm, there was no way that we'd complete the entire trek under daylight, but ultimately I convinced @mrs.turbodb that coming back in the twilight wouldn't really be that bad - after all, we were just following the canyon, and it was all going to be downhill.

She grabbed her head lamp - a good thing, given that I didn't think I'd need mine - and we set out at a good clip, ready to be wowed.

Knight Canyon starts right away as a deep open gorge hemmed in by massive slopes of Paleozoic strata. The most impressive area is the high, conspicuously striated southern wall, the rocks belonging to a Permian sequence of sedimentary rocks known as the Owens Valley Formation. It is composed of dozens of long, thick, alternating layers of limestone, shale, and sandstone, stacked from the wash all the way up to the canyon rim. Each stratum is a time marker, like a tree ring. Since this sedimentation took about 28 million years, each of its approximately 50 strata represents a modest 560,000 year slice of time. If you walk up to the south wall and touch any portion of it, your fingertip will cover only about 300 years of earth history—something like one heartbeat of eternity.

It was - to be fair - a dramatic start to the hike, and I'm glad we spent a few minutes at the strata, taking it all in, before continuing on up the canyon. The existence of an old road for much of the way made for reasonably easy hiking, though several sections - near now-dry springs - were overgrown with rabbit brush. Bushwacking through was a bloody experience for the one of us that had worn shorts.

The springs being dry also meant - naturally - that they were not as dramatic as they'd obviously been when our guide had been written, so we skirted by as quickly as we could, on the lookout for a mining camp nestled along the wash. Finding it was easy - a yellow tractor standing guard in the middle of the wash - and though there's little left of the rest of the camp, we marveled in the discovery of the tractor.

It was here that the road - now primarily a burro trail - began to fade, along with the light of the day. Still, we pressed on - a mere mile to go until we reached the terminus of our hike at the upper springs.

We never made it.

Three quarters of a mile later - with the sun below the horizon and a stunning display of color overhead - we decided to head back the way we'd come. We'd hiked for one hour and forty-eight minutes, covering just under 3.5 miles. We were clearly headed back in the full-on-dark.

It took us ninety minutes to make the trek down the canyon, a single, low-power headlamp held by whoever happened to be the lead hiker for any given section. With no moon and an already-faint trail, we took solace in the fact that while it may not have been ideal - or dare I say "my brightest idea" - there was little chance that we'd get lost. And so we continued on to the truck.

By 6:30pm we'd arrived - my twice-scraped shins the only casualty of the ordeal - and headed back down the road to find camp. We'd passed through a quarry of white crushed gravel on our way up, and its platforms seemed like as good a spot as any to setup for the night - my hope that the easternly views would present a stunning sunrise the following morning.

Temperatures were still in the mid-70s, and having prepped cold dinners prior to embarking on the journey, all we had to do was pull our pasta salad and quiche out of the fridge, in order to enjoy it in our camp chairs with a view of the starry sky and the occasional headlight making its way slowly across the Panamint Valley floor below.

It had been a wonderful first day. But it wouldn't be our best.

The Whole Story: Retracing Panamint Valley's Nadeau Trail

Love Death Valley? Check out

the Death Valley Index

for all the amazing places I've been in and around this special place over the years.

Very nice trip!!!

Great writeup and look forward to next edition. Have been to the Defense Mine and Lookout City in the Argus range but need to explore more of the range!

Wonderful hike up the old stagecoach route that is accessed on way up to Lookout City. When the road to Lookout city first hits the ridgetop and switches back to east, you can see the route heading west as it drops back into the canyon .

It ran from Skidoo to Darwin , but is closed road since it drops down into the Navy base on its way to Darwin.

Spectacular views down into Darwin area and amazing rockwall construction along the route. Great hike. Bet chinese built it too.

Thanks Greg! Hopefully the next couple stories can bring back some good memories for you as well! ?

Look forward to the stories.

Being a hiker you will enjoy the stagecoach route I described.

It was so well built, it could be driven today if didnt cross navy land.

Give half a day to get to the top of Argus range and the navy base gate.

Thanks again, Greg

Born and raised in Trona... your trip has warmed my heart with memories of the beautiful Pannimint Valley.

Makes me smile to hear that you enjoyed the story Donna! I just posted the second part of it here: Craters, Canyons and Cabins - Nadeau #2, and I hope you enjoy it just as much. 🙂

Great report! We were just at Kopper King last weekend and saw the adventuretaco entry. Really enjoyed all the history and thank you for clearing up the mystery of those concrete blocks sitting on that big slab at the Onyx mine. I haven't done my trip report yet, but will post our Panamint Valley adventures soon.

Hey Lina, Glad you enjoyed the trip report and your time up at the Kopper King. Pretty chill spot up there, and hopefully we’ll end up back there some day!

Would love to see your report when you post it. Reply to this comment when you do and I’ll give it a read.

Hi Turbodb - I posted a report on our first day in the Panamint Valley here:

4x4nearandfar Panamint Valley Trip Report

More to come. Lina

Well dang, always wanted to hike to see what that was, oh, a tractor, nice. guess i won't be hiking there now.

It's a pretty great hike regardless of what's at the top of the wash Kenneth - I'd recommend it even if the tractor doesn't interest you as much as it did us!

Hello, i mean i noticed the look of some kind of yellow equipment, i love seeing that, when i seen your pic, i new it from google earth. I was like oh darn, i wanted the surprise of seeing what it was. LOL. It's all good. i was just joking around. You have a great site, loved the pics.

Let these people find this themselves. Your need to be seen is ruining our lands. They vandalize the cabins, throw out beer cans, and geotag for any clown to see the locations. I ran your ass out of the desert if I ever see you.

Hi there, Sorry to hear that you feel the way that you do. I understand the concern that you have, but I - perhaps obviously - disagree with your approach. In fact, I'm a huge steward of our lands, cleaning up everywhere I go, and doing my best to promote responsible recreation. For locations that are well known - like this trip that you've commented on to the Nadeau Trail - I do give general locations, but for others that are not well known/written about on the internet, I redact and obfuscate locations in order to keep them special. You can see many examples of that from a more recent trip I've taken to Death Valley, here: Hiking Saline Valley.

You'll also notice that I never share coordinates (see Do you have a GPX for that?), so figuring out where I was takes a bit of work - more work than most are willing to put in - to figure out a route, and I've found that those who are willing, are generally like-minded folks who are also good stewards.

To say that we should just keep all places on public lands secret is - in my opinion - doing more harm than good, and is being disingenuous. How did we - literally you and I - find out about them? Someone mentioned them, or hinted at them, and we thought they were interesting. We researched. We set out to explore. What makes us better than others? Nothing.

Anyway, happy to chat more if you have additional points. But I'm not sure threatening people (while not even being willing to leave your name) online suggests that you are the best steward of our lands, in general.

Stay safe out there!

My husband and I were introduced to Panamint Valley in 2003. We fell in love immediately, and have returned at least once most years. Love reading your adventures. Not sure if you realized you captured the Panamint Shark in one of your images!!

Thanks Stacey, it's always so nice to hear when folks enjoy the stories, and it triggers memories or loves for them! Hopefully you've had a chance to read all the parts of this particular trip, but if not, I'll share a couple links for you:

I've never heard of the Panamint Shark, but now I'm super curious. A quick back look through the photos and I didn't see it. Can you let me know which photo showed it, or share a photo of it (you can attach an image to a comment).

Thanks!