This page was archived from https://moabrockart.org/the-birthing-rock-an-analysis/, in order to preserve the valuable content should it be removed at some point in the future.

FEBRUARY 5, 2023

Rory Paul Tyler

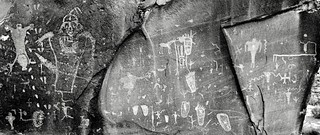

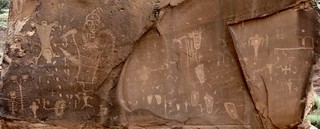

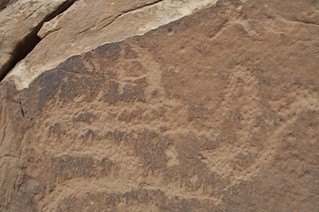

Figure 1. The Birthing Rock, Side 1. North-facing wall.

Preface

The Birthing Rock rock art panel is the best known of a rock art complex which includes at least seven local Basketmaker Indian fertility and/or female related rock art panels. They are on canyon walls and boulders along the Colorado River/Kane Creek corridor; six miles of rugged terrain near Moab, Utah. I discuss the Birthing Rock in my slideshow “Mother Earth: Feminine Symbolism in Basketmaker Art” and in my interpretive manuscript, Codicon, but a more focused look is appropriate for this well known but complicated and mysterious site.

The Mother Earth slide show examines the Kane Creek rock art complex and the Birthing Rock, but does not discuss the panel’s details as closely as I do here. In this essay I apply the Codicon’s interpretations to the Birthing Rock, focusing first on individual design elements, then on the identity of an iconic female design, the roles it might play en concert with other glyphs, especially hunting symbols, and finally the topographic associations between the Birthing Rock, its vicinity, and its art. (Topography is a largely neglected factor in most rock art interpretation.) Many of my interpretations are stated in a matter-of-fact style. If you want to know why, I explain my reasoning for each one in the Codicon. I hope that helps. If my speculations and inferences start getting a little wild I will try to point that out…if I notice.

Introduction

Almost all, if not all, of the rock art on Moab’s Birthing Rock was made by the Basketmaker people of the northeastern Colorado Plateau. The presence of Basketmaker rock art on most of the Plateau indicates that this culture lived in the region for almost 2,000 years, c. 1,000 BC to 1,000 AD. Major cultural shifts occurred around 300 -500 AD (Pecos designation BM II and BMIII, a proposed BMI not having been found) and the Anasazi transition in the San Juan Basin around 800 AD. The quantity of rock art indicates that the largest populations of Basketmakers were found around Moab in the north, along the San Juan River drainages in the central region, and along the Little Colorado and Puerco River basins in the south and southwest. Each area’s bands used idiosyncratically local rock art designs, but there are many other designs and design elements that were similar and used across the entire region to express identical concepts and intent. This suggests social intercourse and cultural overlap between and among the different bands of the tribe over a wide area for a long time.

Despite the huge amount of Basketmaker rock art in the region, archeologists have spent comparatively little time or energy in the study of the Basketmaker cultures. This may be due in part to our own culture’s initial fascination with the Anasazi Pueblo builders, c. 700-1300 AD. Academic interest in people who built houses and made pots, familiar objects to us, led to a preference to award grants to those who would exhume these cultures. There was also a general presumption in the archeological ‘trade’ that rock art is too enigmatic, impossible to interpret, and a weak tool for cultural analysis. I disagree with those last notions.

Corn appeared in the southeast corner of the Plateau around 1,000 BC and spread with the Basketmakers through most of the region by 500 BC. Whether the Basketmaker culture evolved from the resident Late Archaic culture (c. 2000 BC – 0 AD) or came from elsewhere is not known. (See my blog post Finding Culture in Moab’s Basketmaker Rock Art) As the Plateau’s first farmers, the Basketmakers are assumed to have had a relatively reliable supply of food. This presumably allowed them a chance to create art and, for whatever reason, many artists took that chance. The Archaic cultures may have rivaled the Basketmakers in art production but, because so much of their art was painted and not pecked, it has not withstood Time and quantitative comparisons are moot. (The range and variety of Archaic art has not been well-studied either.) Basketmaker art portrays many normal human activities and interests including, for example, hunting, fighting, fertility, and astronomy. Fertility and hunting are the prevalent themes at the Birthing Rock.

Starting with a small number of identifiable Basketmaker symbols I inferred chains of associations that seem to fit within parsimonious patterns of intent. (I discuss my interpretive methodologies in the early part of the Codicon.) This would not have happened if Moab’s Basketmaker rock art wasn’t exceptionally representational when compared to most other cultures, if I hadn’t been a lifelong Joseph Campbell reader, and if I hadn’t been lucky enough to stumble on the Rosetta Panel in the upper reaches of Moab’s North Fork of Mill Creek, known as Left Hand, in the summer of 1997. (Except for ‘atlatl’, ‘bow-and-arrow’, and ‘Birthing Rock’, I coined the names of all glyphs and panels in this essay.)

The Rosetta Panel

Almost all of my interpretive hypotheses begin at the Rosetta Panel. I have written about it in the Moab’s Ancient Artists, Game Drive, and Mother Earth slideshows, the Codicon, and blog posts. The Rosetta Panel contains two Basketmaker designs that are fundamental to all my of my inferences, advances, and conclusions. First is the Predator, a mountain lion-like figure with short ears, long tail, and a specialized track design. The Track’s design elements include a segmented sole, tined toes, and detached claw marks. The second design is the Moab Vagina, an inverted U with a dot at either end of the line.

A lion-like Basketmaker Predator and its Track, and the Moab Vagina symbol appear on both the Rosetta Panel and the Birthing Rock. Hundreds, perhaps thousands, of Predators and Tracks are found in the Basketmaker region. There are, to my knowledge, only four Moab Vagina glyphs. One is on the Rosetta Panel, one is at the Portal, the cleft where the Colorado River slithers into the nearly unfathomable chasm that comprises its latter course, and two are on the Birthing Rock.

The relationship between sex and hunting on the Rosetta Panel is unmistakeable. A line starting at the Predator’s face ends up in the symbolic chasm of the Moab Vagina petroglyph. Why the relationship between hunting and sex should receive such emphasis eludes me. A similarly close association on the Birthing Rock reiterates the Rosetta Panel’s message. Although the Birthing Rock’s depictions are less blatant than the Rosetta Panel’s, the interplay between fertility and hunting is plain to see in both.

Figure 2. The Rosetta Panel. A lion-like Predator and its Track, upper left. A line extends from the Predator’s face and, after a metamorphic meander, connects with a phallus which penetrates a Moab Vagina symbol.

Figure 3, above. Rosetta Panel. Predator and Tracks

Figure 4, right. Rosetta Panel. Moab Vagina and phallic symbol.

Figures 3 & 4. Details of the interpretive elements mentioned in Figure 2.

Predatory Basketmaker zoomorphs and their Tracks exist throughout Basketmaker territory. The range of the Moab Vagina glyph is limited. It only appears around Moab. This suggests that, while Moab Basketmakers shared key symbols with an extensive network of other Basketmaker bands, they also possessed a distinctly idiosyncratic symbol which set them apart from other Basketmakers in the region.

Moab Basketmakers’ exclusive association with this design suggests that other Basketmaker populations may have had exclusive fetishes, totems, and symbols which informed and represented a local identity. Similarly unique designs do seem to occur among other Basketmaker bands, but what those symbols and their ranges might be is largely unknown. Given the Moab Vagina as an example, this is a topic that may be worth studying.

It also may be that the magic of the Moab Vagina fetish was shared with others in the Basketmaker world. If you sought fertility help you might make a pilgrimage to Moab. The absence of Burden Carrier glyphs at this site argues against, but does not preclude, this appealing surmise. Burden Carrier glyphs often appear in Moab and elsewhere near active cultural sites like game drives and astronomical displays, but none appear to be traveling by the Birthing Rock.

The Birthing Rock

The Birthing Rock is a boulder about 12 feet square, on a steep slope above Kane Creek Canyon, four miles from the confluence of Kane Creek and the Colorado River. There is rock art on all four sides of the boulder. The cover photo, Figure 1, records Side 1, the north-facing facet of the boulder. Figure 5 shows Side 2, the east-facing side. Figure 6 shows the south-facing, Side 3, and Figure 7 shows the west-facing side, Side 4, with its heavy patina. Fig. 44 shows the Birthing Rock ‘in-context’.

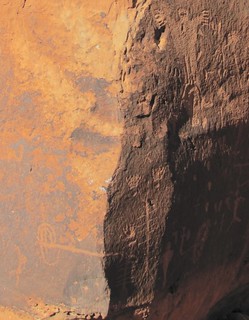

Fig. 5. Birthing Rock, Side 2, east facing. 8

Figure 6. Birthing Rock, Side 3, south facing. A small Bow-and-Arrow hunting scene on the left and a fairly generic collection on the right.

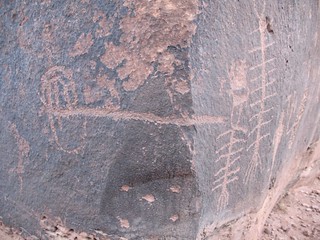

Figure 7. Side 4, west facing. This simple and elegant panel was defaced in April 2021 AD.

Figure 8. This vandalism includes phallic, fascist, and racist output indicative of the marker’s entrolled frame of mind. Most of the heavier marks were removed by the BLM, but they haven’t done much to restore the visual integrity of the patina.

Figure 9. The Moab Vagina at the Portal. This is the largest vagina illustration in the region. Two examples of this icon appear on the Birthing Rock.

For me, the strongest bonds exist between the Moab Vagina at the Portal and the highly abraded Moab Vagina glyph on the Birthing Rock. The Portal Vagina glyph was created where the river enters the precipitous chasm of the canyon lands, evoking comparisons to the birth canal and associated mysteries. Between the Portal and the Birthing Rock there are at least five other female- themed panels, the densest such collection in the region.

I don’t see a narrative line embedded in or associated with the Birthing Rock. Rather, its meanings seem to pivot on an interface between feminine and masculine symbols, inspiring an array of relationships, some stronger, some weaker. The Birthing Rock, Side 1, is the wellspring of these relationships and that is where this discussion will soon lead…but first.

The glyph was probably surrounded by a painted human body. There is a sash-like accessory hanging from her hip. (See the Mother Earth slideshow for the entire group.)

Figure 10. Birthing Rock. Mother Earth glyph.

I call this, the most arresting glyph on the Birthing Rock, Mother Earth. The design element between her legs is commonly misidentified as a baby to whom she is giving birth. A closer look reveals an inverted U shape with two dots at the terminal ends, the Moab Vagina design. A macroscopic view allows one to consider the Portal Vagina and the Birthing Rock Vagina as the alpha and omega of a fertility display in a four mile gallery of ancient art. The use of an identical design at both ends of this ‘female passage’ anchors and informs the canyon’s feminine symbolism.

A macroscopic vantage can provide a terrestrial reference which may be useful for analyzing a glyph, panel, or site. Such a viewpoint is seldom used by rock art autures, autodidacts, avocationals, archeologists, etc. The tendency to analyze one panel or even one glyph at a time without considering the companion glyphs or the physical surroundings discounts and ignores too much. I rely on a macroscopic analysis at the end of this essay to discuss to what extent a male/female dichotomy is illustrated by this terrain and its art.

Figure 11. Birthing Rock, Side 1, Mother Earth, Moab Vagina

The glyph is heavily abraded. This may have been the result of frequent rubbing, painting, or both as a way to “harvest magic” from the image. For whatever reason, the intensity of this abrasion indicates that the assumed magical properties of the totem were called upon repeatedly for a long time.

The labor and care lavished on this image was probably occurring at the Portal Vagina as well. The energy expended at these two sites may have supported and sustained a presumed metaphysical matrix that empowered female fertility icons and female-themed panels along the canyon’s walls. This is speculation but I don’t think it’s too far from the mark. (See Mother Earth slideshow.)

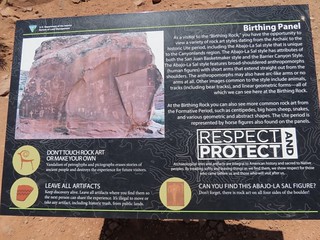

Figure 12. BLM interpretive sign. I will refer repeatedly to this sign and to the interpretive examples it propounds. Be forewarned, I disagree with most of these interpretations and consider the very existence of this sign a threat to the site and its art. More on that later.

Figure 13. Birthing Rock, Side 1. I will discuss the panel starting on the right side, address the central facet, and finish on the left facet before moving on to Side 2.

Figure 14. Birthing Rock, Side 1, detail. The generic anthropomorph, upper/left, is still holding some red paint on its body. (According to the BLM sign this is an example of an ‘Abajo-La Sal style’ glyph.) There is an abrasion on its chest as evidenced by a small dimple. Some of the paint and stone have been harvested, possibly in a ceremony or as part of a personal fetish. Some glyphs were placed over earlier figures indicating that the site was used for many years. The linear glyph, upper/right, is an enigma.

Figure 15. Side 1, detail.

Figure 16. Side 1, detail.

On Figures 15 and 16 the anthropomorphs are carrying atlatl throwing sticks in front and atlatl spears by their side. This is an unusual stance. I can’t think of any similar example. Most atlatl poses are more active.

Figure 15 is notable for the care and quality of the fletching design element on the end of the spear. Spear depictions are rare enough. Seen in a sedate context and with the fletching illustrated in such detail is rare indeed.

The Birthing Rock’s hunting images include three atlatls, at least two examples of a bow-and-arrow hunter shooting a sheep, a game drive scenario on Side 2, and two Trapman depictions which seem related to a hunting panel three miles away. I will go into these in detail, but suffice it to say that the sum of the intent of these elements adds up to a substantial amount of hunting magic. This must be considered as a defining interpretive factor at the Birthing Rock as surely as the female fertility theme. It is easy to become so enamored of the fertility theme that the hunting theme gets overlooked. But, as the plethora of hunting elements and tableaus shows, they matter a lot.

The three atlatls on the Birthing Rock require thought and discussion. The atlatl was the region’s primary projectile weapon until the introduction of the bow-and-arrow between 300 AD and 500 AD, the time of the transition between the Basketmaker II and Basketmaker III cultural expressions (Pecos designations). Because the art at the Birthing Rock includes both of the weapons there is a good chance much of the art appeared within that time frame. Having a relatively solid date is an invaluable tool for placing cultural stages on a timeline. This hard date gives us a temporal base line for rock art placement that few other prehistoric cultures can provide. For example, much of the art here is unlikely to be Archaic since the Archaic cultures had no knowledge of the bow-and-arrow. And it probably isn’t Ute art because the atlatl had been out of use for over 800 years by the time the Utes arrived on the Plateau. So, this solid date diminishes the chance that Archaics or Utes were the among the site’s artists, something which is stated as fact on the BLM’a sign. Personally, I can see no specific design or design element on the Birthing Rock that is diagnostically Archaic or Ute.

Most of Moab’s atlatl users sport the ‘Cat-in-the-Hat’ headdress, the single-appendage headdress seen in Figure 16. (See Cat-in-the-Hat in the Codicon) This design element disappears at about the time of the bow-and-arrow’s appearance, one of the changes in cultural practices that must have occurred at the time of the atlatl/bow-and-arrow transition.

On the Birthing Rock, both atlatl men are moving to the left, toward the new born boy on the other end of the rock. The child’s mother has an atlatl laying across her belly. This combination of elements resembles some sort of mystical rite or mythical legend, like our culture’s well-known fantasy of three magicians following a star to the birth-scene of an infant Savior. We cannot know what stories and/or metaphysical dramas compelled the Basketmakers, but here we see a dramatic portrayal of these compulsions in the art they left behind.

As upon the Rosetta Panel, hunting and fertility are well represented on the Birthing Rock. I note this connection but don’t try to interpret it. There are anthropologists, psychologists, ethnologists, mythologists, therapists, etc.ists, who are more informed and equipped than I to address these matters. Pointing out that this relationship exisiss and was illustrated by Basketmaker artists is an essential first step in a parsimonious explanation, whichever ‘ology’ one tends to.

My opinion, stated in the Introduction, is that the origins of the Birthing Rock’s art are mostly Moab Basketmakers. The Bureau of Land Management interpretive sign, Figure 12, posits ‘San Juan Basketmaker’, ‘Barrier Canyon Style’, ‘Abajo-La Sal’ and ‘Ute’ art styles as appearing on the Birthing Rock. The BLM sign employs old and suspect references as lynch pins of provenience and cultural identity. The earliest academic assignation of Basketmaker culture came out of the 1927 Pecos Conference which systematically coined, arranged, and adopted many anthropologically inadequate concepts that are in use today. The Pecos framers conceived their system when archeology was in a primitive state and knowledge of the Basketmakers was sketchy at best, so we shouldn’t be too hard on them. You’ve got to start somewhere. Common Pecos terminology for Basketmakers includes ‘Pre- Puebloan’ and its cousin, ‘Formative’. (‘Formative’ is used on the BLM sign.) However, the Basketmakers had no skill or tradition in building Pueblos. ‘Pre-Puebloan’ presumes a cultural continuity which hasn’t been demonstrated. The related designation ‘Formative’ also presumes cultural continuity from Basketmakers to Pueblo builders. Here are some questions. How could San Juan Basketmakers ‘form’ and adopt an alien architecture and culture, including bean agriculture and technically sophisticated pottery between 750 and 850 AD, which is how long it took in the San Juan basin? Why didn’t Moab Basketmakers ‘form’ a similar culture at the same time? There are no Anasazi Pueblos in Moab and Moab’s Basketmakers never ‘formed’ a Puebloan culture. Why not? This is not the place to discuss these. I address them in the blog Finding Culture in Moab’s Basketmaker Rock Art.

William Lipe and Sally Cole did a lot of useful field work from the 1970’s into the 1990’s; Lipe as an academic archeologist and Cole as a pioneering rock art researcher. Influence from the Pecos Conference, Lipe, and Cole can be found on the BLM’s interpretive sign. To my knowledge, neither Lipenor Cole reliably affirmed the territorial ranges and/or cultural interfaces of the different Basketmaker divisions. Lipe, did most of his work in the 1970’s under the territorial, technical, and monetary limitations imposed by academic grants. He identified two areas of Basketmaker activity in his grant locales, one centered on Mesa Verde and another around Kayenta, Arizona. Lipe’s published work did not, to my knowledge, extended its identification of the Basketmaker realm north to Moab or west to the Petrified Forest despite the thousands of Basketmaker glyphs in these areas. Little other work has been done on the Basketmakers since then, and Lipe’s ’Mesa Verde’ and ‘Kayenta’ aslsignations are still accepted as limiting territorial defaults. Cole drifted somewhat from Lipe’s strictures and proposed an ‘Abajo-La Sal’ culture, a blend of San Juan Basketmakers and Archaic peoples in the region of the Abajo and La Sal Mountains (Somewhat like I suggested in the aside on Page 3). To my eye, her proposed diagnostic traits are short on determinative detail. More importantly, to my knowledge, she does not integrate ‘Abajo-LaSal” into the wider Basketmaker presence on the Plateau.

While the Moab Vagina fixes the location of one Basketmaker band, the Cat-in-the Hat, Figure 16, was used by several bands and defines the range of the northern Basketmakers more clearly than an ‘Abajo-La Sal’ designation. The Predator and its Track define the range of the entire Basketmaker sphere of influence more accurately than Lipe’s ‘Mesa Verde’ and ‘Kayenta’ designations. (Cynthia Irwin-Williams artifactual collections probably present a more

accurate portrait of the ancient Southwest’s demographic and cultural continuums than the Pecos Conference, Lipe, or Cole, all to whom, by the way, I give thanks for their work and devotion.)

Figure 17. Birthing Rock, Side 1. A small owl in the upper/left corner of the facet. There are two other owl glyphs along Kane Creek Canyon. They are larger and use a different style.

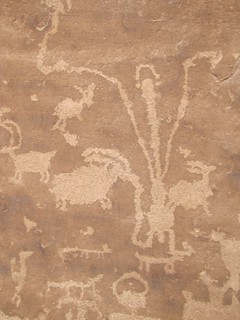

Figure 18. Birthing Rock, Side 1, center. The central facet of the Birthing Rock contains a figure with an unmistakable Moab Vagina design in an anatomically correct position. This glyph removes any lingering doubt one might have had regarding what this design represents. The zoomorph attached to the female’s shoulder has sheep-like hooves.

Figure 19. The Grandmother. The Moab Vagina is perfectly made and anatomically placed. There are vagina glyphs in other cultures’ rock art but this design is unique to Moab.

Who or what is this figure? A midwife, doula, guardian spirit, grandmother (which is how I like to think of her)? We will never know. Her membership in the the Birthing Rock’s Trinity of female figures emphasizes the essential roles women performed and shared in the rites, rituals, and practice of bearing babies.

There are sandal imprints superimposed on the Grandmother. They are complex and carefully done, resembling the finely detailed construction of Basketmaker sandals, rather than the comparatively crude workmanship of later Anasazi and Ute weavers. This suggests that the sandal prints were made during Basketmaker III times, 300 AD – 900 AD.

Bird tracks going up the wall resemble heron tracks. A heron glyph is next to the baby boy on the next facet of the panel. There are many heron and heron glyphs in the region near the river and along local streams. A fish-spearing heron could be an apt totem for an atlatl-hurling Archaic or Basketmaker. (There are few cranes in Moab.)

Figure 20. Birthing Rock. Side 1, center facet. Except for Side 2, most of the art on the Birthing Rock does not seem to interact directly with the neighboring images. A narrative pattern is not apparent among the Birthing Rock’s messages. Different pecking incidents from different ages add to this confusion. At far/right, for example, a heavily patinated sheep is running, a common hunting theme. To the left, the bright footprints are from a much later era. One of the prints has six toes, a supernatural characteristic. I don’t see anything that ties the two images together in age, culture, or intent. The figure between two sandal tracks, low/center, might be construed as a Bird Head atlatl thrower from the San Juan Basin, but that’s a stretch.

Figure 21. Birthing Rock, Side 1. Left facet. The left facet of the north facing wall contains a variety of images. It is the heart of the Kane Creek rock art complex.

Figure 22. Birthing Rock, Side 1, left facet.

I assume that the close proximity of these various hunting and fertility design elements says a good deal about a shared message or intent. (The term ‘symbolic interchange’ comes to mind but I’m not brave enough to go there.) There were certainly stories and rituals connected with all of these figures. But, as I said, I can’t see a story line that stands out or represents a unifying theme or pattern. (Maybe it illustrates a marriage. He goes hunting while she watches the kids. Which begs the question, are better hunters better husbands?)

Figure 23. Birthing Rock. Side 1. Mother Earth. Many people interpret this as a birthing scene but, as noted in Figure 10, this entity holds a Moab Vagina between her legs, not a baby. The apparition’s mysteries may speak to eternal fertility, the immortal Spirit of Life giving birth to Life. (Wild guess!)

The entire glyph is heavily abraded. Abrasion of this quality was often created to hold paint. I suspect that this figure was painted and repainted by generations of women seeking the blessing of motherhood with the aid of this totem. The nearby presence of hunting paraphernalia might indicate a preference for a boy, but that is speculation.

To Mother Earth’s right there is a deeply incised and smoothly abraded, set of baby steps going up the rock. I can think of no other such trackway.

Attached to her foot is a human figure. He may be wearing the Cat-in-the-Hat headdress and carrying an atlatl, but neither is assured.

Figure 24. Birthing Rock. Side 1. The Mother.

The large figure, I call her the Mother, is giving birth. Below her belt is a severed umbilical cord and a one-armed baby boy who is attended by a long-legged Heron and two Cat-in-the-Hats to his left. The tears coming from her eyes are probably due to labor pains. This design convention is also used by San Juan Basketmakers. Joe Pachak taught me about the ‘tears’ motif. This may be a partial clue to the origin of one of this panel’s artists. This is the only likely ‘San Juan Basketmaker’ element I see on this panel. (I have seen similar markings on Fremont Indian panels.)

Her headdress and necklace are unusual and hard to assign a style. The large atlatl laying across her belly indicates early Basketmaker provenience.

To her left, going up the wall, next to the baby tracks, are a set of rabbit tracks, the only such set I know. Our culture has a trained-in bias that equates rabbits with fertility. Did the Basketmakers have a similar analogy?

See Figure 47.

25. Birthing Rock, Side 1. The Mother.

The large atlatl lain across the Mother’s tummy makes an eloquent contribution to the interchange between fertility and hunting.

A seated figure, intersecting the atlatl point, is an enigma.

Figure 26. Birthing Rock. Side 1 & 2. Side 1 and Side 2 are tied together by a horizontal line that reaches from the Trapman glyphs on Side I into a game drive scenario that informs Side 2. The feminine/fertility motif is abandoned on Side 2, but the hunting motif remains strong. The bow-and- arrow has displaced the atlatl on Side 2 and Side 3 of the rock.

Figure 27. Birthing Rock. Side 1. Trapman glyphs. These figures are often misidentified as

‘centipedes’ (including on the BLM’s Birthing Rock sign). They actually represent a trapping entity and/ or intention I call Trapman. Nets and fences were often used, along with confining topography, to capture prey. The Trapman figure is a symbolic expression of such artifacts, terrain, and intentions.

The largest Trapman figure in the Moab region is three miles upstream from the Birthing Rock in a location that goes from being a steep and open area, ideal desert bighorn habitat, to a very narrow and vertically restricted canyon where sheep could be confined and captured.

The twin emblems at the top of the larger Trapman glyph resemble the tined toed/segmented heels of many Predator tracks, but the execution of these glyphs is not clear enough to make an assured identification. If they are Predator tracks then their close affiliation to the Trapman design makes a further statement about the predatory energy that abides in the Birthing Rock.

The emblem above the lower Trapman image resembles images elsewhere that conflate a sheep or deer glyph with the symbol of a Predator or its Track. This kind of symbolic conflation is a common trope among Basketmaker artists.

Figure 28. Kane Creek. Trapman. This Trapman glyph, the largest of its type, is where Kane Creek Canyon goes from a wide open area to a confined, narrow canyon; a good place to put fences and nets in order to trap animals. What the anthropomorph is doing here is not clear. The sheep is rearing back in alarm as if it perceives a threat. This Trapman glyph is stylistically identical to the Trapman glyphs on the Birthing Rock. If, like the supposed metaphysical matrix between the Portal Vagina and the Birthing Rock Vaginas, we assign a symbolic cohesion between this image and the Trapman glyphs on the Birthing Rock, then this might identify the Birthing Rock as a nexus where male and female energies were believed to meet and meld. That’s a guess. (See the Game Drive slideshow for an analysis of this site.)

Figure 29. Hidden Valley. Birthday Sheep. I called this the Birthday Sheep because it looks like birthday candles on a small cake. Obviously a dumb name, but there you are.

This conflation of a sheep and a Predator track is obvious.The sheep’s body doubles as the Predator’s heel. The tined toes have clearly defined claw marks at their termini. Six toes suggests supernatural qualities.

This image resembles a similar conflation on the Birthing Rock, Figure 27. The conflation of Predator symbols and Prey symbols in a single image occurs throughout the Moab region and speaks to how the Basketmaker culture may have alloyed the two archetypal entities, Prey and Predator – Life and Death, into a single symbol, a theological/metaphysical awareness and grateful acceptance of their everyday reality. (There I go again!)

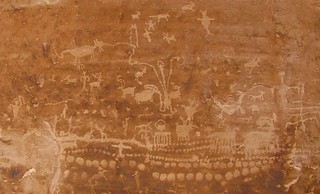

Figure 30. Birthing Rock, Side 2. The south-facing facet of the Birthing Rock is busy. It is almost entirely about hunting. The two major lines, the thick one above and the fainter zig-zag below, which runs into a rough surface, form a containment corridor which advances a drive-lane interpretation (Figures 36 and 38). Linear design elements and/or natural topological formations often combine on a panel to depict confined corridors where the prey can be contained, captured, and killed. That is the message here.

Figure 31. Birthing Rock, Sides 1 & 2. The horizontal line leads from the Trapman glyphs, right, to an ovoid design around the corner. I have seen similar ‘domes’ in contexts where they could be interpreted as traps, gates, etc. Hunting installations and artifacts were often built, used, cached, repaired, and re- used at the same site by generations of hunters.

Figure 32. Arches N.P., Dark Angel site. A possible example of a dome-shaped hunting artifact, this one perhaps attended by a man. At upper/left, a sheep is impaled by an atlatl. Below the sheep, and facing the other direction, is a short-eared, round-footed, long-tailed Predator with a similar patina and pecking style. Multiple styles and patinas at this site speak to its long use as a hunting magic location.

Figure 33. Birthing Rock, Side 2. This side of the rock hasn’t the clarity of execution or overt symbolism of Side 1. Nonetheless, it has several interesting features. At the top of the thick line is a man holding a stick, a tool, or a bow. Further down the line a hunter is shooting a sheep with a bow-and-arrow. Most telling, there is a line of sheep tracks in the dark patina at the bottom, fleeing right to left, where a long- tailed, short-eared Predator awaits.

Figure 34. Birthing Rock, Side 2. A small man at the top of the thick line is holding something. It may or may not be a bow-and-arrow. The missing part of the rock may have held an image that expanded the story.

Figure 35. Birthing Rock, Side 2. About 1/3 of the way down the thick line is a small tableau; a bow- and-arrow hunter shooting a sheep.

Figure 36. Birthing Rock, Side 2. A line of sheep tracks runs across the bottom of the facet, contained between the linear glyphs and rough surfaces above and below ( Figure 33). When sheep or deer are running, the dew claws come down and make two small marks at the rear of the hoof. In this case, the sheep is running pell-mell toward a zoomorph in the lower/left corner. It has the short ears and long tail of a mountain lion.

Figure 37. Birthing Rock, Side 2. A short-eared, long-tailed, spade-footed mountain lion watches as the sheep arrive in its domain.

Figure 38. Birthing Rock, Side 2. The light scratchings of some vandals don’t disturb the visual impact of the tableau much. Still, it would be a simple matter to make the scratches virtually invisible with a touch-up application of Tite-Bond semi-soluble glue and water, about a 1-to-12 mix, with matching masonry color added. See Connie Silver’s works of art restoration at Sego Canyon and Buckhorn Wash, Utah, and her reports on the same in BLM libraries. It’s not rocket science.

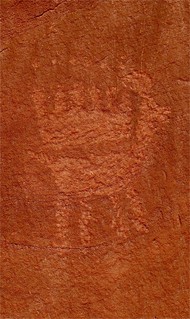

Figure 39. Birthing Rock, Side 3 (See Figure 6). The south-facing wall of the Birthing Rock contains two small panels. This one, in the lower/right part of the rock, gives little away. The man at upper/left has a large hand common in Basketmaker art. At center, there may be a spear or atlatl fighting scene but that is not certain. At lower/right a possible Cat-in-the-Hat may be holding a possible dagger. That is also speculation.

Figure 40. Birthing Rock, Side 3. A bow-and-arrow hunter shoots a sheep, extending the hunting theme to Side 3. The lighter patina and deeper pecking style on the sheep were obtained in a re-pecking effort. This suggests that the panel was a hunting totem for a long time. The comb-like design below the sheep and hunter may be a gate or fence image guarding against the sheep’s escape, repeating the contain and capture motif seen on Side 2 (Figure 30). If the Birthing Rock was a hunting site I don’t know how it worked. The art here may equate to positive visualizations where hunting magic and prayers were ‘stored-up’ by the devout in hopes of good fortune later on.

Figure 41. Birthing Rock, Side 4. The west-facing side of the Birthing Rock is notable for this simple, elegant design on a heavily patinated surface. This picture was taken in 2014. There was some light vandalism, but not bad.

Figure 42. Birthing Rock, Side 4. The panel seen from a different angle. The wavy line may represent a containment symbol, like a fence or net, reiterating the intent of the wavy line seen in the bottom of Figure 30. The dots at the ends of the wavy line may represent spools that were used to store a net. That is speculation.

The track between the two triangle figures possesses the segmented foot of many Predator depictions. It may represent a cat, a bear, a bear/cat, man, or some other sort of Predator, but Predator in any case.

Figure 43. I first saw the Birthing Rock in the spring of 1994. I saw one small example of vandalism there until the interpretive sign and ‘protective’ fence were installed, sometime around 2018-19. Both are easily seen from the road. They draw attention to a site that most people drove past. It has been vandalized three times since it got ‘protected’. This example from April 2021 is the worst. Roads, for obvious reasons, are the greatest danger to rock art, but the BLM doesn’t seem to know that.

Topography

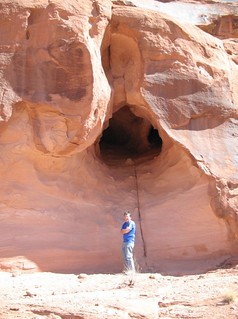

Local topography can be an essential part of site analysis. There are many sites where topology and art combine to create scenarios. At the Birthing Rock site a small cave and a phallic boulder contribute to a possible geo-sexual tableau.

Figure 44. Birthing Rock and vicinity. The Birthing Rock is at lower/right. A phallic boulder is at center. At upper/left is a small cave that suggests a vagina and/or womb. Once you know of the cave and boulder the sexual analogies are unavoidable. It may have been this topological convergence of male and female analogs that encouraged ancient artists to place fertility themes and hunting themes together on the convenient pallet of the Birthing Rock

Figure 45. The Birthing Cave is less than 300 feet from the Birthing Rock. The analogy to female genitalia is obvious.

The cave splits into two passages reminding me of many North American myths about the ‘Warrior Twins” born by Mother Earth to protect, defend, and teach the people…or something like that. I’m actually a little surprised and disappointed that the birthing scene on the Birthing Rock doesn’t show twin brothers.

Figure 46. Rock Hard. The phallic analogy to ‘cock and balls’ would be hard to miss if you had already learned a vagina designation for the Birthing Cave. A similar geo-sexual scenario can be posited between the tower at the Solstice Snake and the nearby Bean Hole Cave. See the slideshow Moab’s Ancient Astronomers.

Figure 47. Birthing Rock, Side 1. Baby tracks, left. Bunny tracks, right. 52

Conclusion

In this essay I start with a granular technique, parsing a glyph’s specific meanings before I try to integrate that design into a larger interpretive blend. By drilling down on symbol and intent I hope to mine a pallet of hypothetical elements that may be of use in defining a larger context. Once an interested person begins to ponder the Birthing Rock, consideration of a larger context is almost unavoidable. These clues might come in handy for such an undertaking.

The Birthing Rock holds a lot of information about fertility, hunting, and the relationship between hunting and fertility magic, a relationship that may include the Portal’s Moab Vagina symbol, the Kane Creek Trapman. Knowing these elements may help someone, someday, shed light upon more of the big picture. For now, that level of illumination is beyond me.