This series of posts was archived from Mining Morrisonite in order to preserve the content should that blog be taken down in the future.

I discovered the Christine Marie Mine in the Owyhee Canyonlands on my Owyhee Out-and-Backs trip. Upon returning to my visit and looking for more information about the mine as I put my story together, I was delighted to find the entertaining and informative story about several years of its development, from the guy who made it all happen - Eugene Mueller.

Please do enjoy this content, and I encourage you to visit his original blog (if it still exists) as well as his storefront - The Gem Shop, Inc. - to show him support.

Note: No modification has been done to the content of the posts, though some portions have been reformatted to display correctly here.

Rats, Mice, & Snakes: A Better Mousetrap

Tuesday, January 25, 2011

Occasionally, Jake's trap caught things other than mice.

The mouse population varies greatly from year to year in the desert northwest. One year their population exploded so much it prompted a warning from local health officials for miners and others who worked and lived outside. That year, when I stood outside quietly in the sagebrush about half an hour after sunset, the ground would shimmer with activity. I could not actually see anything in the growing darkness but sensed that something moved over there, and then something moved over here, and then again something moved somewhere else. It was just creepy. In the morning, after the mice went to bed, the evidence of their presence in the cabin was everywhere. There were lots of mice.

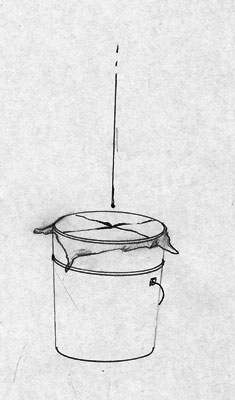

Above is Jake's better mousetrap.

I didn’t – and still don't – usually include a bunch of mouse traps with my mining supplies, and store-bought traps are not be very effective anyway. Jake taught me how to build a better mouse trap out of materials often found in any mining camp. All you need is a 5 gallon bucket, a paper bag, some string or rope, and a little peanut butter. Put about 3 inches of water in the bucket. Stretch the paper over the top of the bucket and tie it on with string, rope, or wire. The trap should have a smooth surface like a drum but does not have to be as tight. With a sharp knife make two straight right angle cuts in the paper all the way across the covered surface of the bucket. These cuts should cross in the middle of the bucket (see drawing). Where you put the trap does not matter – the mice will find it. However, a string must be hung directly over the center of the bucket. The string should end about three inches above the surface of the paper and be liberally coated with peanut butter. You must also provide a ramp for the mice to get to the edge of the bucket. Any old piece of wood, cardboard, or pile of rocks will work. A mouse will smell the peanut butter, climb up on the edge of the bucket, step onto the paper stretched over the bucket with water in it, fall in, and drown.

Now you must understand what peanut butter is to a mouse. It is the ultimate food – a 5 star restaurant, the meal of a lifetime, a meal that will never be forgotten, something that cannot be passed by. Its smell is intoxicating, alluring, like violets in springtime or Christmas cookies backing in the kitchen. The scent must be followed until its source is found.

Gene's hat rests on a hook in the cabin.

A mouse traveling through the sage brush and getting a faint whiff of peanut butter will change direction and head for it. As the smell gets stronger, it will find the bucket and the ramp up to the rim. On the rim the mouse encounters a small dilemma. While the excitement of the peanut butter straight ahead is almost overwhelming, a small wave of a sense of danger enters the mouse’s atmosphere. As it moves onto the paper, its weight causes the paper to dip toward the water below. This is alarming for the mouse because he knows the peanut butter is up on the string and that he will have to reach up to get it. Most mice move back to the rim, stand on their hind legs, and sniff the peanut butter on the string -- so close yet so far away. They then move out onto the paper a little further, stand cautiously on their hind legs again, and sniff. When they bring their front feet down to the paper, the paper bends, and they fall into the bucket. The overwhelming desire for the peanut butter versus the perception of danger is fascinating to watch and provides numerous entertaining examples which parallel our own desires and their consequences. One morning that year I found 28 drowned mice in the bucket.

Rats, Mice, and Snakes: Ancient Evidence

Friday, February 4, 2011

Sheepshead Ridge provides a breath-taking view.

The last 4 miles of road to the edge of the rim overlooking Shepherd Ridge trends generally north over the lava plateau just east of the Owyhee River Canyon. A lone tree can be seen on the Canyon’s rims horizon while traveling this road. No other tree can be seen for many miles in any direction. Overlooking the rim another tree can be seen on the top of the ridge above the two mining cabins below. No other trees can be seen for miles except along the river 2000 feet below where the road drops off the plateau onto the ridge.

The Christine Marie mining claim is about half way down the canyon in steep slopes of loose rocks. The welded tuff host rock is shuddered and sliding sown hill toward the river. This is both a wonderful and hazardous situation for mining -- wonderful because the rock is all broken and easy to mine; and hazardous because of the constant potential for rock slides. The jasper found here is the best there is, but there is very little of it. If the rock were not broken up like this, the deposit would not be worth mining. All of the cracks in the rocks are ideal places for rats, mice, and snakes.

While working on the Christine Marie claim, I was constantly encountering old rat nests in the cracks in the rocks. It actually became a joke among us miners that working on the Christine Marie meant constantly working in rat shit. The deeper into the mountain I worked, the larger the cracks between the rocks became, and the bigger the rat nests became.

Loose rocks clutch the wall in this exposed digging area.

Many times I would find bones and skulls of deceased rats. I would place these skulls on the rocks around the area I was working until the mine pit took on a ghoulish appearance. I then stopped.

In one massive nest I found a leg and wing bone of a large bird – probably from a rare occasion where a rat won a battle with a buzzard. Buzzards hunt this ground every morning and evening. I also would find twigs and branches of pine wood. I thought nothing of this until one day I realized there is not a tree anywhere near where I was working. How far would a rat travel to bring a stick of wood back to its nest? The closest tree to the workings on the Christine Marie mine is up 1000 feet near the upper cabin – almost ½ mile away. I seriously doubt that a rat would travel that far from home.

I kept some of the sticks of wood and had them tested. The turned out to be 600 years old. So the rats nest that the sticks were in was about that old. 600 years ago the Morrisonite area must have been much wetter with more trees and vegetation.

The mine resides in the Oregon desert.

Rats, Mice, & Snakes: The Rats I Could Not Find

Friday, February 18, 2011

This picture shows one of the cabins with the dozer to the left.

I heard the noise and reached for my flashlight again. I pointed it at the rock slope behind my bunk and searched for the rat. There was no sign of a rat anywhere. I climbed down off my bunk to look around. All was quite and peaceful -- no movement or sounds anywhere.

Notice the elevated mattress.

I was living in one of the upper cabins -- the one that Jake built. Jake was living in the other cabin built by Tom Caldwell in about 1976. Jake was working in the old Big Hole pit about 5 switchbacks down the canyon, and I was working on the Christine Marie further below and to the south. The bed in this cabin is built up off the floor like the beds in all the other cabins. This is done to minimize nightly encounters with animals especially snakes. The bunk in this cabin is built higher off the floor than the bunks in the other cabins. A frame attached to the cabin wall supports the front and the rock wall in the back holds a sheet of plywood on which sits a covered box-spring mattress. This is about 5 feet off the floor and about 2 feet from the roof rafters. Snakes seek warmth and can crawl right in with you if you are sleeping on the ground. It makes for a cozy bunk with a little window in the side wall so you can see the morning even before you get out from under the covers. The problem is that it is a little difficult to get in and out of. It is necessary to have a way to climb up into it and climb down out of it. This is not a pleasant experience in the middle of the night looking for a noisy rat.

After another day of hard work it happened again. I was awakened from a dead sleep by the noise of rats. I was beginning to think I was dreaming the noise or hearing something outside. I rejected the idea because the noise seemed so clear and close when it woke me up. The rock wall at the head of my bed slopes gently to the roof rafters at the back of the cabin. To freeze a rat there with the flashlight should be easy, but I did not see one.

Gene revisits the cabins years later.

This went on for 3 or 4 nights, and I started to complain about my situation to my friend Jake. He has had much more experience living outside than anyone else I know. He was a little curious about my story and came over to take a look around. He asked me if had looked under the box-spring mattress. I said no. We both lifted the mattress and there were three half--grown rats cuddled in a nest under where my head would be on the mattress. I was sleeping inches from them. They were probably scared motionless until I fell into a deep sleep and then started moving around waking me up.

I slept better that night.

Rats, Mice, & Snakes: The Snake That Came To Dinner

Friday, March 4, 2011

The road snakes down the middle from the cabins way at the top.

I was working on the road to Christine Marie claim. This was a tedious and slow process because of the steepness of the road. When I finished for the day, I would leave the dozer as close to my work area as possible and walk up to the cabins for the night. Tonight would be my first and only experience with teleportation.

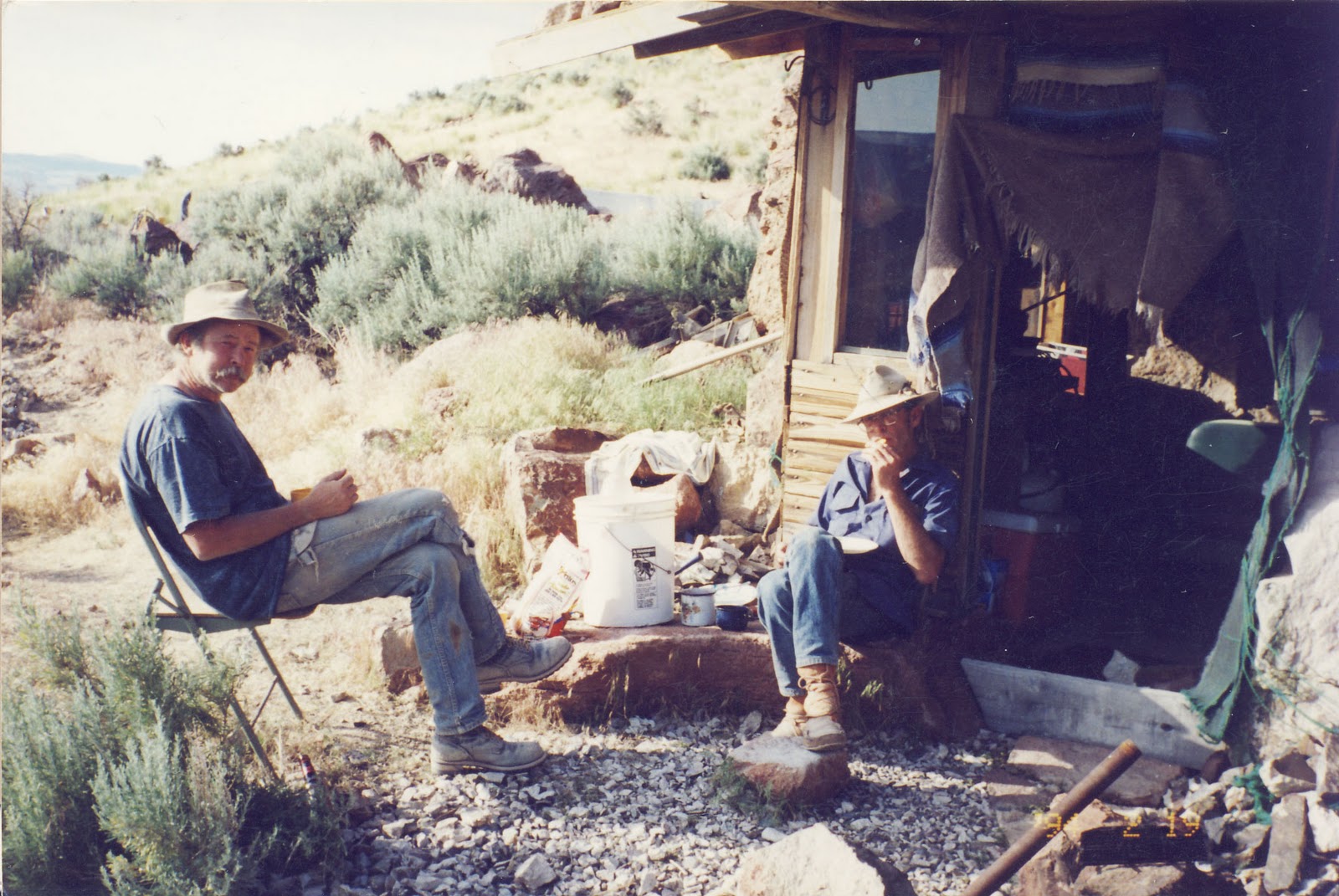

Gene and Jake enjoy a meal in the hot sun.

I was sitting in my chair next to my propane cooking stove looking out my cabin door, exhausted. I remember that I was slumped down in the chair with my feet out in front of me trying to find the energy to get up and add something to the potatoes and onions already cooking on the stove. The weather was changing outside and a weird wind was blowing. It would be colder tomorrow. Much to my astonishment a rattle snake slithered in front of the door headed to the west. It moved about half way across the flat area outside the cabin door opening and stopped. It lifted its head about 6 inches and looked inside the cabin. I watched the snake and thought, "Just go on to where ever you are going and leave me alone." The snake, frozen, looked directly at me. I was slumped down so far that my right hand could touch the ground. I picked up a small stone from the gravel floor and tossed it at the snake to encourage it to continue on its way. The snake came right at me – straight into the cabin. The next thing I knew, I was standing outside the cabin looking in through the door. The only sound was my potatoes and onions cooking on the stove.

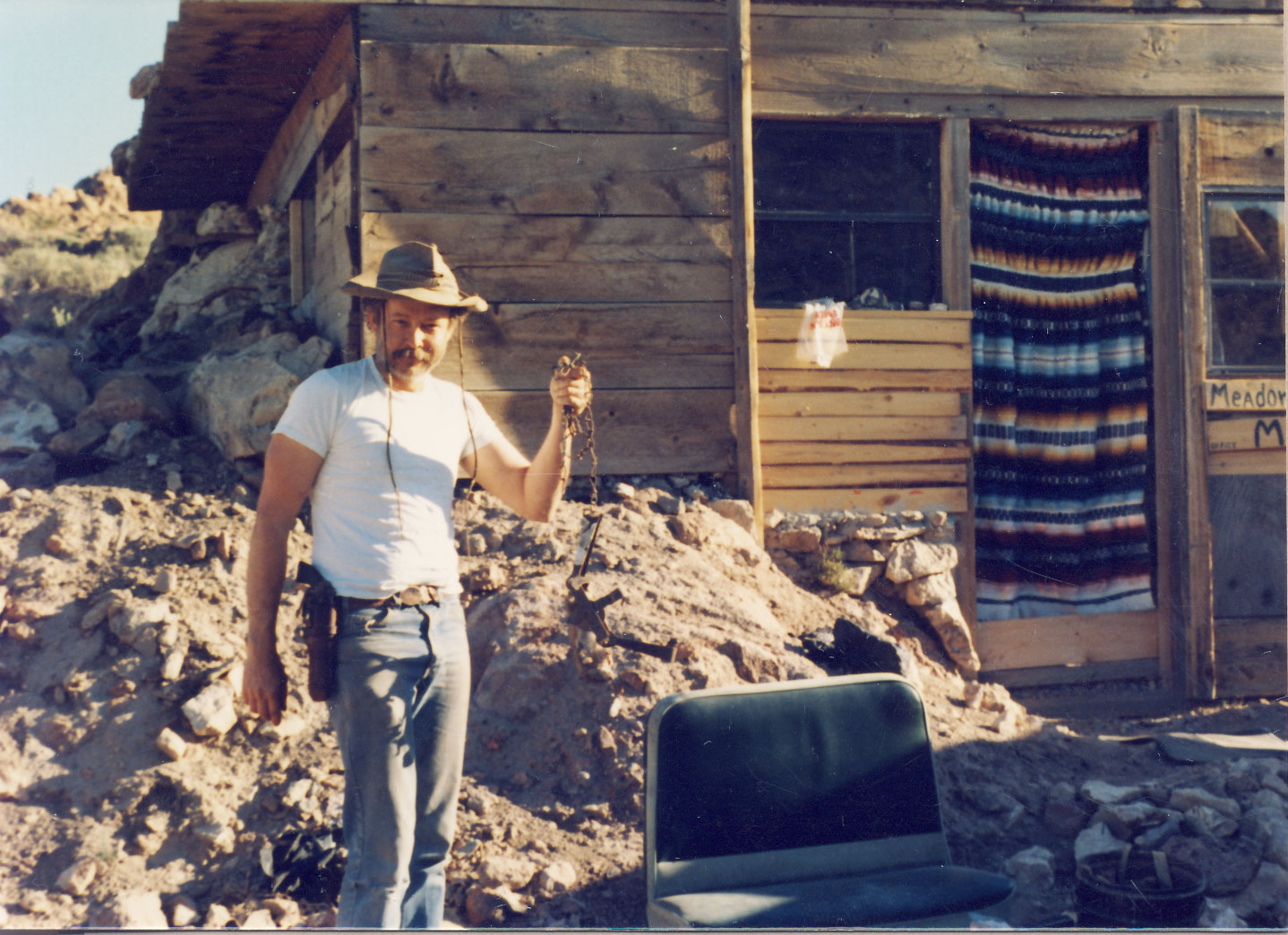

Gene poses with a wire trap.

Now, I have been interested in the ideas postulated by science fiction writers for some time. The idea of teleportation – disassembling your body molecule by molecule and reassembling it at another place or time – is interesting if not plausible. To this day I have no memory of any thing between those two moments. One moment I was slouched in a chair tossing a pebble at the snake, and the next moment I am standing outside my cabin, my heart pounding furiously, looking in with no snake in sight. Perhaps I teleported to a safer place.

Slowly my problem came into focus. My supper is cooking on stove in the cabin with the rattle snake. I am outside the cabin and don't know where the snake is. I went to find my gun. Luckily it was in the truck and not in the cabin. Then, another problem came into focus: my explosives were all packed in various containers under my bunk -- a nice place for a snake to hide and a nasty place for bullets to fly.

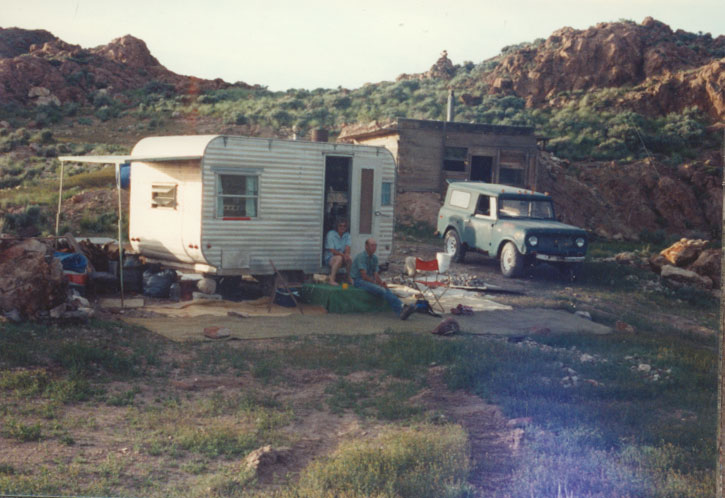

Jake's tent, the Scout, and Gene's cabin at the Christine Marie mine.

This was a different time -- before the Oklahoma City bombing. Buying and using explosives was no big deal if you knew what you were doing. The major concern for the miner was where to storage them and how to keep them dry. Keeping them under your bunk may sound a little foolish, but a miner always sleeps in the driest place possible, and storing explosives under the bunk was practiced quite often by individual miners.

The road, rebuilt every year, near the Jake's Place Claim.

Bullets and explosives don't mix, but having a rattle snake in my cabin was unacceptable. I poked my head inside the door and tried to see the snake. The potatoes and onions smelled good but there was no snake visible. When I was certain I could step into the cabin safely, I did. This provided a better view but still no snake. I took one more step into the middle of the cabin and saw him curled up under my cooler in the back corner opposite from my explosive, but. I was still concerned about the possibility of bullets ricocheting into them. I climbed up on my bunk to shoot down at the snake and hopefully leave the bullet in the dirt. The bullet went through him twice. I picked up the snake, took him outside, and nailed his carcass to the outside of the cabin. I was hungry and had not invited any guests.

Roads: Getting There

Friday, March 18, 2011

This view shows the mountainous destination.

The fork leaves the highway.

There is not mention or location listed for Morrisonite in the Western Gem Hunters Atlas. The Book of Agates published in 1963 simply states that, “Morrisonite can be found near the southern end of the Owyhee Reservoir.” Even though Morrisonite has been collected since the 1940’s, relatively few people have been there or know exactly where the deposits are. The remoteness of the area is legendary among old collectors and a good four-wheel-drive vehicle is necessary to get there today. If you were to go to the southern end of the Owyhee Reservoir and start looking for it, it might take you a few days to find it.

The sign at the right fork.

This is how to get there if you want the adventure, but please be warned it can be a dangerous trip. It would be best to go with two vehicles and plenty of water. Leave yourself plenty of time also.

The lava beds lie in the distance.

The road to get there starts out as Jordan Crater road and goes west to Highway 95 at M.P. 12 ½. This is 12 ½ miles south of where Hwy 95 crosses from Idaho into Oregon and about 6 miles north of Jordan Valley. This road was an improved gravel road for about 10 miles to the split in 1986. Today the road has been improved all the way to Jordan Crater and to the Owyhee River. At about 10 miles there is a fork in the road with the right fork continuing toward Jordan Craters and the left fork going to a ranch. In 1986 the road was unimproved from this point on and contained numerous mud holes, rocks, and other hazards. In 1986 the 29 mile trip from Hwy 95 to the canyon rim took about 3 hours. Today, it is considerably faster.

Clouds hover above Blowout Reservoir.

There are several other roads that cut off the main road, mainly to the north. Continue generally west with Jordan Craters and Tea Pot Dome in your sights ahead and slightly to your left. After you pass Blowout Reservoir on your right – the dam parallels the road – you will come to a cattle guard. The road splits on the other side. The right split goes north down Birch Creek to the Owyhee River and the left fork goes to Jordan Craters. Before you cross the cattle guard you will see a road going to the north along the fence. At this point you are about 4 ½ miles from the canyon rim. This is not much of a road.

The infamous gate awaits.

Follow this road to the corral where you come to a gate. Go through the gate, leaving it as you found it, and continue for another four miles generally going north. This is very rough unimproved road and you can actually walk the four miles faster thank you can drive it. There is one other fork in the road about 1 mile from the rim. Take the left fork staying on the left side of the lone tree on the horizon. This will get you to the canyon rim, 29 miles from Hwy95, overlooking Sheepshead Ridge and the two cabins below.

Notice the tree to the right in the distance.

Do not attempt to drive down to the cabins without inspecting the road first and being sure of your four-wheel-drive vehicle and your ability to drive it. The road may need some miner repairs before proceeding. I have seen many people get to the rim and refuse to go any further.

If you want to walk down from the top to the Jake’s Place Mine, just follow the road over the hill and down about four switchbacks. The Christine Marie is down another four switchbacks and back to the north about ½ mile. This is a minimum two hour hike. The mine on the Christine Marie is about 1000 ft. below the canyon rim.

Prepare for the end of flatness.

Rats, Mice, & Snakes: The Will to Live

Thursday, March 31, 2011

The dozer working in the Christine Marie mine.

It was a particularly bad day. First, the Scout would not start. Then, I was working on the road with the loader about 5 switchbacks down from the cabins above when I lost control of the right track. I had to climb to the top to get some tools only to find when I got back to the loader I did not have all the tools I needed. After several trips up and down with more tools I figured out the break slave cylinder was stuck causing the track to freeze. By this time it was too late to do any work. No jasper today!

The mice were not particularly bad this year but it was time to set up a bucket trap anyway (see my blog post about a better mouse trap). I looked around at my supply of buckets and discovered I did not have a bucket without a hole or crack in the bottom. I had begun drilling holes in the bottom of the buckets to make them easier to pull apart after stacking them together. Also, continually filling them with rocks tends to crack the bottoms. Anyway, I did not have a bucket that would hold water to drown the mice when they fell in. I made the trap and resolved that I would have to take care of the mice every morning.

Sitting in my cabin after dark, feeling exhausted and depressed with the day’s events, I watched an energetic mouse let its desire for the peanut butter on the string overcome its sense of danger and fall into the bucket. The mouse scurried around the bottom of the bucket and tried to climb the bucket walls every way it could. It would stand at the bottom of the bucket wall and jump up the side as far as it could scratching at the smooth plastic wall before falling in a heap at the bottom. I had placed the bucket in the corner on the ground but it was not quite level. Because the bucket sides are tapered one side of the bucket was slightly less steep than the other. The mouse discovered this after numerous attempts to climb the walls, but by this time it was exhausted and laid quietly in the bottom of the bucket for 10 or 15 minutes. It started again. The mouse approached the side of the bucket that was less steep, jumped, and clawed at the plastic wall to no avail. It rested again. It ran across the bottom of the bucket, jumped up to the wall, and pushed off the wall propelling itself a little higher and a little closer to the paper hanging down at the top. The mouse did this 5 or 6 times before falling silent. I thought it gave up. Much to my surprise it tried this again sometime later. This time I saw the paper flicker as one of its front feet touched the paper stretched across the top of the bucket. A little later it tried again -- the paper bent slightly more towards the bottom of the bucket. Then silence. The mouse was nearing the end of its endurance. It hooked a claw on the paper pulling it down where its other front foot found a hold on the edge of the paper, and it scrambled out never to be seen again.

I decided it had been a pretty good day after all. The sun had played tag with big white fluffy clouds all day, and it was not too hot for my many climbs up the hill. Maybe there would be some jasper tomorrow.

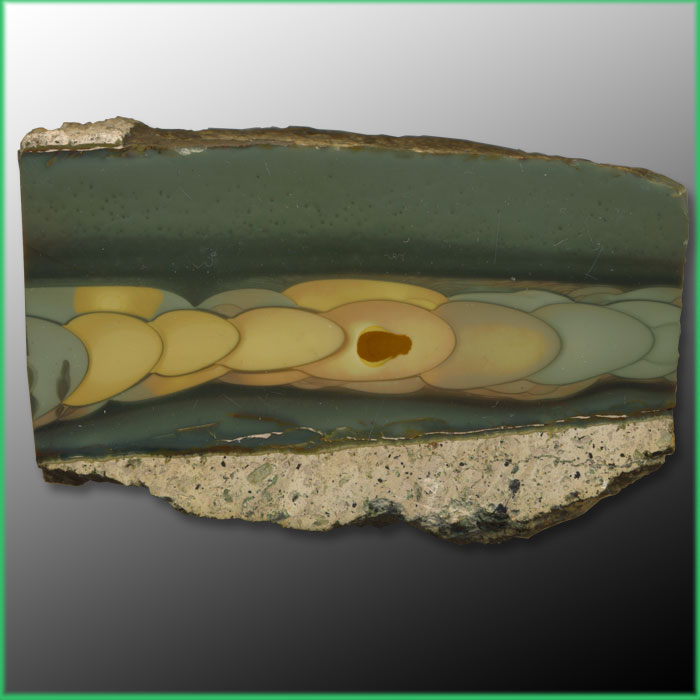

Here are some polished pieces of Christine Marie Morrisonite.

Roads: Three Days

Friday, April 15, 2011

It was late spring and Jake and I were anxious to get back mining Morrisonite. We had been making plans for weeks and decided to make the trip out to the mine together. I arrived in Homedale, Idaho after 3 days driving from Wisconsin. We spent several days making final preparations -- diesel fuel, propane, water, and food was packed everywhere. I was pulling my black trailer, and Jake and Bev were pulling their small house trailer.

We planned on leaving Monday morning and arriving at the mine Monday afternoon. Sunday’s whether forecast warned of a big storm coming over the mountains with colder temperatures on the way. Monday morning came with a low gray sky but no precipitation, so we left. Our desire to get out there trumped our trepidations about the weather. The turn off onto Jordon Creators road is about 60 miles south of Homedale and about 1300 ft higher in elevation. When we turned onto the dirt road the lower sky was spitting a mixture of sleet and rain. I suppose we could have turned around but we were on our way - we were determined to get there. The first 10 miles of dirt road are not a problem even if it is raining a little. After that there would be no turning back, especially with both of us pulling trailers. At the 10 mile split the rain let up a little, and we just kept on going. The road deteriorated fast and we both started sliding in the mud but we kept moving. The rain came back with a great deal of force but we persisted up the low hill to the flats on the far south west end of the Mahogany Mountains. There are some long stretches of soft ground here, and it was not long before we were stuck. Jake’s trailer was half in the ditch tilted at about 20 degrees. My truck and trailer were in similar positions a little further back. We got out, looked around, and decided we were not moving until the ground dried out enough to get some traction. The ground here contains some Bentonite clay which makes the mud greasy and practically impossible to drive through even with 4-wheel drive. We spent the rest of the day in Jakes trailer listening to the wind and occasional rain. Even sitting was a little uncomfortable because of the slant. That night we slept on titled beds hoping for a better tomorrow.

The morning broke gray and windy with no rain. This was encouraging because the wind dries things out fast in this treeless country. We dug a few drainage ditches from around the wheels of our vehicles, put some rocks in the mud for traction, and waited. The sky was threatening rain again, but it did not rain, and about noon we decided to try again. After a couple of adjustments we were moving. The road improved some with rocky stretches between mud holes. Mud holes are not too hard to get through as long as there is hard ground on the other side – although, it is somewhat trickier when you are pulling something. The technique is to have the proper momentum and still allow for maximum traction. We made it to the corral and were feeling optimistic that we could make the last 4 miles when it stated to rain again. The road from the corral to the rim is so rocky that speed cannot be used to your advantage in the mud. The only way to drive this part of the road is slow whatever the conditions. We made it up the little rise after we went through the gate, down a shallow draw, and around onto the side of a gently slopping hill where Jake’s truck and trailer slowly slid off the road and got stuck. I was a little further back and still had some traction. I saw a place where I could get off the road, pulled up in the sagebrush, disconnected my tailor, maneuvered my truck in front of Jacks rig, chained our trucks together, and proceeded to throw mud everywhere with our spinning tiers to no avail. After some consideration we resolved to spend another night in the mud and hope again for a better tomorrow.

The next morning broke like the last - gray and windy with no rain. About noon we tried again and were moving. We both found that with a little more speed we could keep from getting stuck. We were traveling a little too fast to safely negotiate the rocks and were skipping, sliding, and bouncing down the road like rubber balls rolling over gravel. I noticed that one storage compartment door on Jakes trailer had flopped open going over a rock. A few minutes later a white grocery bag full of something popped out into the mud along side of the road. Neither one of us dared to stop. A couple of more bumps and another white grocery bag plopped out on a rock. More bumps, more grocery bags. We made it to the rim, carefully descended to the cabins, and started to set up camp. Three days to go 27 miles.

A couple of days later after things dried out we drove back up the hill to retrieve our food which was still in the white plastic bags evenly distributed along the side of the road for a mile or so. Nothing was ruined or lost. It was a much better tomorrow.

Rats, Mice, & Snakes: The Peanut Butter Jar

Friday, April 29, 2011

The cracks in the rocks were a rat's apartment complex dream.

Jake told me the following story about the rat that lived in the wall of his cabin for many months until it met its sudden and final demise. This particular story came before the rat’s passing – a tale which will be told later.

Jake spent a couple of winters living in the cabin on Sheepshead Ridge above his Morrisonite workings. Spending a winter here is not a casual undertaking. If you are in the Morrisonite area when the weather turns bad in November, you will not be able to leave until March or April of the next year. You are isolated and alone for 4 or 5 months. The only way out would be to walk the 27 miles to the highway. There is no phone service, and no one is going to come and help you if you cut your finger or bring you water if you run out.

Keeping your provisions safe from animals is one concern if you are going to be isolated for 4 or 5 months. In the beams under the roof of the cabin Jake had a metal 55 gallon drum lying on its side with the opening of the barrel out in the open air. Nothing could get into the barrel opening without jumping a few feet from another beam or hanging on to the slippery metal sides of the metal drum. Jake considered it a safe place to keep food supplies, including a large glass jar of peanut butter.

In spring, Jake decided he would go to town for about a week to get supplies. A few days before he left, he opened the new jar of peanut butter, used a small amount, replaced the screw on lid, and put the jar back in the barrel. He came back a little over a week later loaded with goods, ready to be under long siege from daily mining activities.

Some rats prefer a more modern dwelling.

He did not notice right away, but when he did it was with considerable confusion: There, in the center of the lip of the metal barrel, was an empty glass jar with the metal screw on lid lying next to it. It was not that the rat had somehow got into the peanut butter, but that there was no peanut butter in the jar at all. There was no peanut butter on the lid and none in the jar. The jar was clean. There were no smudges or streaks on the glass and no peanut butter footprints in the barrel. The jar shined and sparkled. It looked freshly washed, or rather: like it had never been used. It was pristine.

The rat had devoured the entire contents of the jar and left the jar where he found it. There the glass jar sat, like a trophy or offering to the benevolent peanut butter god that had provided the rat with such a delectable treasure.

Jake still has no explanation for how the rat got into the jar.

I surprised Jake with his dinner.

Roads: Christine Marie

Friday, May 13, 2011

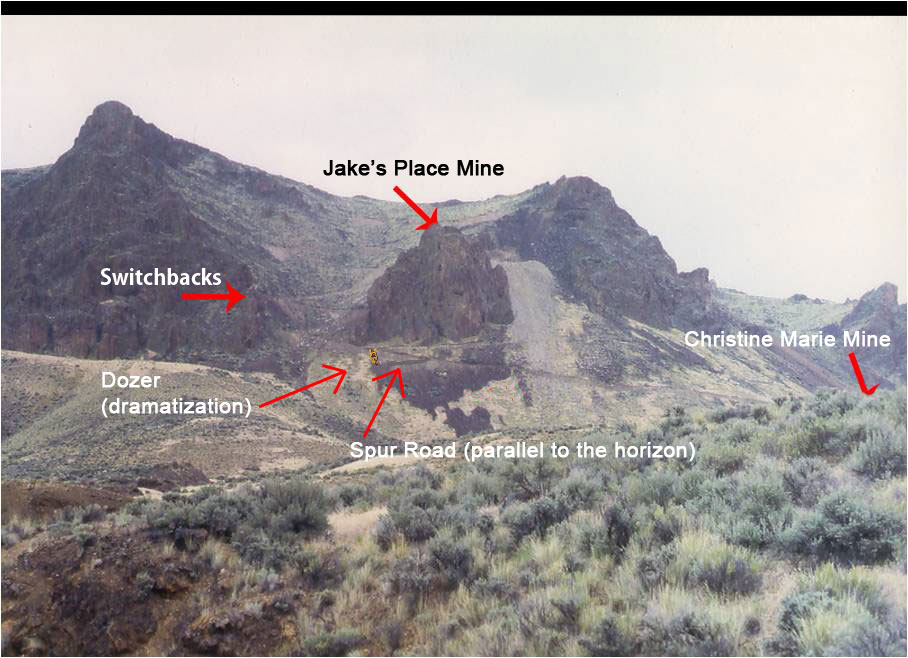

This view shows a close-up of the switchbacks.

The Christine Marie Claim in the Morrisonite area was filed in the early '70s by Ed Brant. The imaginary lines that form the boundaries of the claim draw a 1500 by 600 foot rectangle over very steep rock slides about half way down the east slope of the Owyhee River Canyon. This claim is located further down into the canyon than any of the other claims. The canyon rim is about 900 feet above the center of the claim, and the Owyhee River is about 1100 feet below. The claim’s length runs north and south with its west side boundary line about 300 feet below its east side boundary line. In the mid-70s a small dozer cut a track down the canyon to the north past the Big Hole claim onto the Big Hole II claim, around the cliff below, across the rock slide, back south to the Christine Marie, and up towards the Amy Ellen. This was not a road passable by any vehicle, but it was the beginning of one.

I first visited the Morrisonite area in 1984 at the request of Larry Butler, who told me he had purchased the Christine Marie and Amy Ellen claims from Gene Anthis. Larry was seeking someone to mine the claims and wanted me to look at them and give him a report on what I thought was feasible.

I remember being astonished at the difficulty of the terrain. I understood why so little of this marvelous rock had made it out of this remote location. Many of the people who had worked the area in the past camped on the edge of the canyon rim and walked down the nearly 1000 feet to the deposits. This walk would take an hour or two every morning before a miner could start working. The trip back with any rock might take twice as long. The area below the cliffs on the upper end of the Christine Marie claim is known as the "Nasty Hole" by these early miners -- maybe because it was so difficult to get to.

The jasper on the Christine Marie Claim is exceptional, but there is very little of it. Every conceivable method of access for equipment has been considered. Building a cable winch system from the top of the cliffs and flying in equipment with a helicopter were discussed and quickly rejected. The only real solution that provided a chance of success considering the risks was to build a road down from the top. It was difficult to accept the effort that this would take, but it was the only way to minimize the time required to get equipment, supplies, and rock back and forth to the canyon rim.

The next year I found a man with a sign in his yard that said "D-6 Dozer for hire." I took him out to the claims and we walked the old dozer cuts made years ago. After we climbed back out on top he said to me, "Not me. Not with my machine. It’s too dangerous." Another year later I purchased my own machine - an old D-4 dozer and found a friend of my brother who could run it. After working another claim I had in the area, we moved the machine to the canyon rim to start the road down to the Christine Marie claim. My brother’s friend took one look at the job and said to me "Not me. Not with that machine. It’s too dangerous."

The following year I started working on the road myself with the D-4 dozer. It was a good thing I was ignorant and did not know what I was doing or I never would have done it. It took me two years working about one month each year to build a road barely passable with a four wheel drive vehicle down to the deposits on the Christine Marie claim. I followed the old dozer cut down the canyon creating switchbacks and lessening the steepness of the cut where possible. Once past the cliff, I constructed and entirely new road below the slide rather than follow the old route across it. Some days, because of the steepness of the terrain, limitations of the machine, and roughness of the road, only about 10 yards of road were completed.

I can’t tell you how excited I was to come back three years after I decided to build the road myself with the possibility of swinging my hammer into some rock containing jasper.

Roads: My First Machine

Friday, May 27, 2011

My first steed from behind.

When it became clear that it would be necessary for me to have my own machine to build the road down to the Christine Marie claim, I started looking for used equipment dealers. Through some recommendations I found a man that lived in the small town of Murphy, Idaho who sold used equipment. He had a reputation for good prices and fairness. I went to see him. I explained to him what I needed to do, and that I did not have much money. I also told him that I did not need the machine until next year and asked him if he would look for something inexpensive that would work for me. I gave him $200 for his trouble and left for Wisconsin somewhat depressed.

Nine months later I got a call from him telling me he found a D-4 dozer that I could have for $4,000. He told me it was old but in good shape and had belonged to the Forest Service. I bought and paid for this machine sight unseen -- something I would not recommend doing today.

The dozer rest before another rough day of road building.

The D-4 dozer was exactly as described - old but in good shape. Everything on it worked. There was a hydraulic control to raise and lower the blade. The blade could be angled but only by manually changing it. This required having the machine on level ground, removing pins that held the blade to the frame, moving the machine to line up the blade with a different set of holes in the frame, and replacing the pins -- a process much more difficult than it sounds. And, oh yes, the only naturally level ground in the whole Morrisonite area is the crest of the ridge. The ability to angle the blade allows you to push dirt and rocks to the right or left depending on what direction the blade is angled. This is essential for making a road on steep terrain.

The dozer, like all construction equipment, had a diesel engine but no electric starter motor. You could not turn a key and start the thing up like a car. The machine had a gasoline pony motor. First you had to start the gasoline motor with a pull rope by rapping the rope around the fly wheel and pulling it fast enough to ignite the gas in the engine. Once the pony motor was running well, you engaged a clutch which turned over the diesel engine. Once the diesel engine started you killed the gas pony motor and you were ready to go. If for any reason the diesel engine died, you had to start the process over again.

The driver's seat lacked much as far as visibility was concerned.

There have been vast improvements in the operational mechanisms of construction equipment over the years. This was an older machine with three long levers that came out of the floor in front of the driver’s seat. One operated the clutch and the other two engaged the break to each respective track. The transmission shift lever came up between your legs on the floor in front of the seat. The lever that operated the hydraulics for the blade was to the right of the seat. In order to move the dozer forward to the right you had to move the gear selection lever to a low gear, engage the clutch lever pulling it toward you and disengage power to the right track by pulling the right track lever back. Each of these levers has about a 25 lb. pull force to engage or disengage them. Moving leavers all day long with a 25 lb. pull is a lot of work. Also if your right hand is operating the right track lever, you can not use your right hand to operate the blade. Sometimes it is necessary to pull the right lever with your left hand so you can use your right hand to operate the blade. The operation of one of these machines has been described as watching someone on the machine having an imaginary boxing match with the dashboard of the dozer.

Terry, my brother's friend, running the machine.

The Joys of Mining

Saturday, June 18, 2011

The machine arrives at the drop off point.

Gene is currently mining in Oregon, and provided us with a few vignettes of the operation so far:

I bet Gene's thinking, "Hey, where's the other bucket?"

Gene recently arrived in Oregon and began purchasing all of the relevant supplies for his mining trip to Graveyard Point in Oregon. He went to the gas station to pick up off-road diesel for the machine, but his card to turn the pump on did not work. Gene planned to move the machine the following day, and needed the diesel that day in order to begin work on time. So he managed to convince the gas station staff to call the owner at home in an attempt to fix the pump problem. The owner came in to work, got the pump pumping, and Gene got his diesel on time.

The excavator fords the river.

It has been a wet, cool spring in Oregon. Gene met his appointment to move the machine at 9am on a Monday morning. The machine arrived with only one narrow bucket – Gene had ordered it with a narrow bucket for moving rock and a wider bucket for moving earth. The driver radioed for another truck to ship the bucket to the drop off point later in the day.

Philip happily driving through Succor Creek.

The machine cannot pass the narrow bridge over a canal on the main road to the mine. Gene and company must drive the machine 6 miles on back roads to the mine, which includes wading through Succor Creek. The machine treaded through the creek fine as usual. Then it was Gene’s turn. Gene forded the creek successfully, but nearly got stuck in the mud on the other side. Philip Stevenson drove into the creek next and firmly planted his truck in the muddy bank on the other side. Water began seeping in his truck’s doors and trunk, but left the engine running to keep water out of the exhaust – and by extension, the engine. Gene grabbed the logging chain he happens to keep in his truck for just these occasions and hooked Philip’s truck to the machine. One gentle tug and the truck sprang free.

Gene tugs Philip's truck out of the creek.

The creek leaked out of Philip's truck for days afterward.

Rats, Mice, & Snakes: The Demise of Jake's Rat

Friday, July 1, 2011

Jake's cabin on the ridge.

In a previous blog, "the peanut butter jar," I referred to a rat that lived with Jake in his cabin. This was an old rat, wise to the threat of man, elusive, and an avid collector of things lying around the cabin. This rat caused Jake considerable grief, and he expressed to me several times that if he ever had the chance he was going to put a bullet in him.

Not only do rats cause loss of sleep and disappearance of small objects but they have a particular smell that is not pleasant. The phrase, "I smell a rat," which refers usually to an unforeseen danger or problem, comes from the experience of living in the presence of rats. Any one who learns this smell will instantly recognize it the rest of their life.

This rat had been living in the west wall of Jake's cabin for a long time. We did not know this at the time. Jake also slept on this side of the cabin towards the front. The rat smell was always present.

As if to say, "Jake, don't shoot! I'm no rat!"

Jake kept a hand gun with 22 long rifle hollow point ammunition in the cabin. This ammo can do a lot of damage. One evening the opportunity arrived when Jake saw a small movement in his peripheral vision. His gun was close by so he grabbed it and waited. He saw the rat move away from where it was hiding and fired. The hollow point projectile entered the rat’s rear end and literally turned the rat inside out leaving entrails hanging from the beams overhead in the back of the cabin. This rat was not going to steal any more of Jake’s custom knife handles, special rocks, or utensils laying around the cabin.

After the bullet exited the rat, it ricocheted into a small cardboard box nearby. This box contained blasting caps used to detonate explosives. Why the bullet penetrated the cardboard but did not cause the blasting caps to explode is a matter of divine providence or dumb luck. The bullet was lying in the box next to the dangerous long slender silver blasting caps as if it belonged there.

I asked Jake about the rat parts hanging from the beams in the back of the cabin. He said he left them there.

The gang's all here. Notice Jake's cabin in the background.

Roads: The Broken Oil Pan

Friday, July 15, 2011

The dozer rests from a hard day of road building.

Building the road down the canyon to the Christine Marie claim following the old cat track took me two years -- or two mining seasons (about 2 months). It could have been done faster but I was ignorant and inexperienced both with the intricacies of running my new-old D-4 dozer and working on such steep terrain.

Making the switchbacks was difficult because of the amount of material necessary to push out of the rock slides to make a turn wide enough for a vehicle. In some cases there just wasn't enough rock available to create a smooth turn.

Notice the only level road at Morrisonite running down the cliff on the left.

On one descending stretch between switchbacks I saw the opportunity to lessen the steepness of the descent by extending the length of the section and making the next switchback up against the cliff on the far side. I started pushing rock onto the old cut slowly raising the new road above the old one. I was encountering many large rocks and moved the Dozer over one that just happened to fit snugly between the tracks of the machine. Beyond it the ground was softer and the Dozer slipped down allowing the rock underneath to crush the oil pan which promptly drained its contents.

Agate and Jasper mining is financially risky in the extreme. There is no way to measure or predetermine the quality (value) of the material before it is extracted. A gold deposit can be measured and essayed to estimate the value that could be produced. This value can be compared with the estimated cost of mining and a profit projected. This is not possible with an agate or jasper deposit. For this reason most agate and jasper mining operations are conducted with minimal investment and lots of ingenuity, persistence, and the necessity to solve problems with what you have.

The dozer was tilted downward about 25 degrees -- the slope of the road. The left track was against the rock slide and the blade had a pile of rock in front of it. The whole machine was in kind of a hole with big rocks behind it that I had just traveled over. There was no access to the undercarriage.

Two of the switchbacks on the new road.

Jake was working a few switchbacks above me so I walked up to consult with him. After looking over the situation he wryly suggested I could hire a helicopter to lift the dozer out of the hole and put it up on top where I could work on it!

I have always been amazed and comforted by Jake's ability to suggest multiple solutions to any mining problem. He approaches mining problems with optimism, enthusiasm, and the widest range of possibility. Many times ridiculous or impractical solutions clarify what needs to be done and moves the mind away from a negative situation to a more positive direction.

I dug out the Dozer with a pick and shovel until I could crawl under it. I then carried my tools down from the cabin (600 ft. above) and removed the oil pan. I carried it up to the cabins, cleaned it, and JB-welded it together. Once the epoxy was set, I reinstalled it, put in new oil, got the machine running, and went back to work on the road (about a three day process altogether).

A quick note on mining supplies: duct tape, wire, JB weld, and some rubber -- which in my case is old inner tube, because you never know when you might need to make a new seal -- should always be close by.

The dozer rests in Old Boot Dig on the Christine Marie mine for lunch.

Roads: Driving the Scout to the Christine Marie

Friday, July 29, 2011

The scout is parked in the center next to the cabin, covered in snow.

It became apparent to me while working on the switchbacks that I would never be able to construct them with enough of a radius to accommodate my truck. Even with enough room to back up a few feet there was not enough room for my truck to get around several of the switchbacks. I had to find another vehicle with a smaller turning radius to go up and down from the cabins to the Christine Marie Mine.

I found an old four-wheel drive International Scout with large tires that had been used for snow plowing. It had a few problems (it was so rusted that a piece or two would fall off every mile or so), but had a good V-8 engine. I towed the Scout to the mine and used it to drive from the cabins down to the mine. Even when the road was in its best condition, on the trip down and up I encountered all of the following.

A view of the mine from the dozer.

In the beginning, the drive down after going over the edge is easy but steep. The first four switchbacks have been improved slowly for many years and are passable even with my truck. The approach to the third switchback is very steep and rocky and this switchback’s turn is tight but possible. The fourth switchback turns into the “Big Hole”/Jake’s Place mine. The fifth switchback turns out of the Jake’s Place mine and is on level ground compared to all the other switchbacks.

The next section of the road down the canyon between the fifth and sixth switchbacks is the steepest. The sixth switchback on the lower end is not big enough to make the turn without backing up once, even with the Scout. This switchback is level so other than backing up once, it is not a problem. The seventh switchback is up against a cliff and is very steep. You cannot stop on this turn going down or up. This turn could be made with the Scout if you were careful to be as far left as you could before you turned down to the right. This was a little scary because the drop off to the left of the road after the right turn was severe.

Notice the steepness of the switchbacks.

The eighth switchback is tight but level and like the sixth switchback required one back up to get around it. Sometimes on the way down it was possible to make the turn if you hit the turn just right. The rest of the road goes around the cliff, down across the rock slide from the mine above, and down into the next canyon on the Christine Marie. The rest of the road has three steep places but no more switchbacks.

Driving the Scout up to the cabins is an adventure every time you do it. First you must go up at the proper speed – fast enough to provide the best traction and not so fast as to encourage spin-outs. Approaching the eighth switchback you must stay as close to the drop off on the left as you can and turn right directly into the cliff and stop. This will leave the vehicle slightly uphill. You then either let the Scout roll back, turning hard to the left aligning the vehicle to the next uphill stretch, or put it in reverse and slowly back up to the edge of the cliff. Once in this position you can get a running start on the next stretch and switchback number seven. It is important to get good speed on this section because you cannot stop on switchback seven. If you do stop on switchback seven it is very hard to get going forward again, and it may be necessary to back down to switchback eight and try again. The Scout must be driven fast enough to slide the back wheels around the corner.

Gene working at the mine.

The next stretch up to switchback six is not as steep and travel to it is easy. At switchback six you must stop, back up, and get lined up for the longest and steepest assent on the road. Enough speed is necessary to achieve the momentum necessary to keep from spinning out before you get to the top of this stretch and enter the Jake’s Place mine. The only other spot that can cause problems is the steep area past switchback three. Because you have to slow your speed around the turn, the steep rocky part can easily cause the tires to spin aimlessly after you get around the corner.

One time I decided to check the odometer on several of my trips up and down the canyon. Each time the odometer read ¾ of a mile from the cabins to the mine and 1 mile from the mine to the cabins. The ¼ mile difference is the amount of traction-less tire spinning necessary to get up the steep road to the cabin!

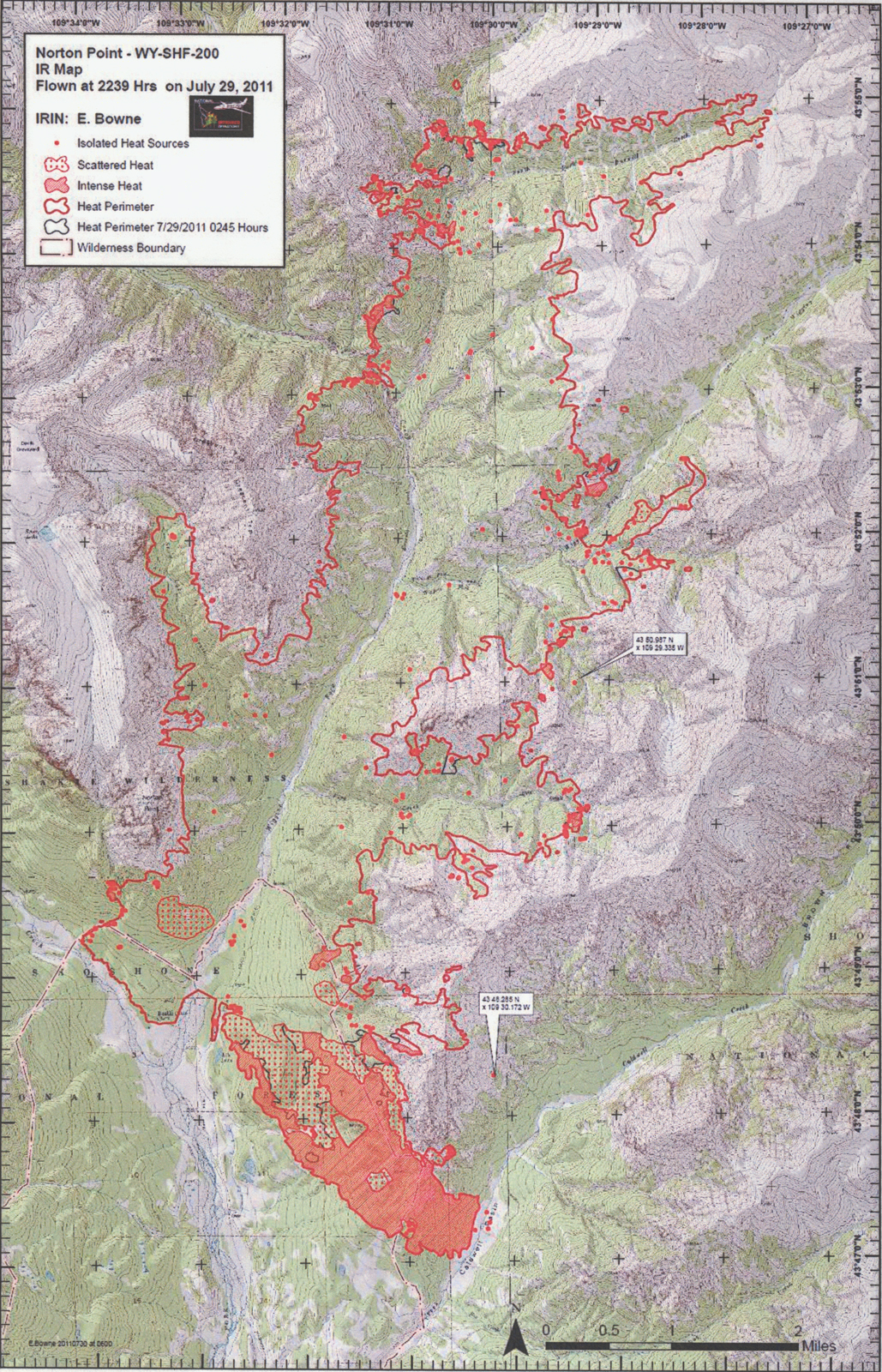

Wiggins Fork Fire

Thursday, August 18, 2011

Vapor cloud from fire 7.25 as viewed from Horse Creek

View of the fire from 3 miles away 7.26

Every year I travel to Wiggins Fork / Double Cabin Campground, Wyoming to collect Petrified Wood and Limb casts. I have done this for 39 years. The Campground is at 8300 feet, and the agate casts form at about 9000 feet. The Petrified Wood is in the mountains at about 10,000 feet. All of these materials wash down the rivers and can be found in the river gravels.

Norton Point, morning of 7.26

This year my wife and I arrived on Monday, July 25th at Horse Creek Campground, ten miles north of Dubois, Wyoming. We had received a message that a small fire had started on Norton Point and that the Forest Service had recommended that everyone leave Double Cabin Campground.

Fires burning on Burn Creek and Fire Creek, east of Wiggins 7.26

On the previous Friday a storm had come through the area with lightening and started a small fire. On Friday it was still burning but not of much concern. On Saturday there was a strong wind, and the fire expanded and started to move. On Sunday the fire moved very quickly down the slope on Norton, jumped Wiggins Creek, and started up the other side.

Burning towards Frontier Creek 7.26

On Tuesday we drove up to Double Cabin and watched the fire all day from the far side of the meadow on Frontier Creek, opposite the fire which moved slowly down the slope against the wind toward the creek. I have never witnessed a forest fire before, and it was amazing to hear and see trees explode into flames as if they were bombed from a mysterious source.

Frontier Creek

The fire stopped at Frontier Creek and Norton Creek, but moved all the way up Wiggins Creek. It also traveled over the ridge and down into Caldwell Creek and was threatening Bug Creek. On Saturday, August 6th, the Forest Service and Fire Fighters held a public meeting where they explained that the fire had so far cost one million dollars but that no one had yet been injured by it. After a little more than a week of the fire burning, Double Cabin Campground was reopened, and we were able to spend four days there. Some of my pictures were taken at that time. On our last day there, August eleventh, the fire intensified and burned most of Caldwell Creek. The Forest Service said they expected the fire to continue until the first snow fall.

Listed below is a first-hand account from Tom Noe who was up Wiggins Creek on Sunday.

Fire intensifying near Elk Lake

Late Saturday afternoon I was camped close to the Frontier Creek trailhead lying under the cap of my truck in the back and working a crossword puzzle. I looked east and saw what looked like a streamer of campfire smoke just across Frontier Creek, rising maybe 150 yards north and upslope of the ranger cabin. It was about 300 yards away from me. I knew there wasn’t any trail over there, and I couldn’t think of any reason why anybody would be camping there; it was dense forest and probably had lots of downed and dead trees. No place for hiking. And why would anybody be starting a campfire at that time of day anyhow? I decided to let Earl, the campground host, know about it. It took a few minutes to walk across the meadow, and when I got to Earl’s rig he was just coming out with binoculars. Somebody had notified him already and he’d just notified the rangers. I told him I didn’t think that was a campfire, and he looked and said, “No, it’s not, and it’s getting bigger.” He said it was probably a lightning strike from Friday night, when we had a storm with lots of lightning and wind. (The tenters next to me had all the stakes in one of their tents pulled up. The only thing keeping the tent down was them sleeping in it!) Earl said a tree had probably been hit then, and it finally got enough oxygen to start burning.

Early view of the fire

Fire approaching Frontier Creek

I walked back to my truck and took some photos over the next few hours. I saw three firefighters head across the creek at 8:30 and took a picture of them. Later, just about dark, one of the rangers drove around to my site and she explained that the fire was close to the wilderness area. If it had been in the wilderness area, letting it burn would be the policy, but it was in the national forest and the campground area had 300 people in it. The Wind River Backcountry Horsemen had a huge gathering, including over 100 horses, the biggest crowd ever in the campground area, and with human safety a concern they had decided to put the fire out. It was about half to 2/3 of an acre at that point. The three firefighters were going to fight it until midnight. Sunday morning a larger team would be coming in. They didn’t think they would need aerial support, but a helicopter at Yellowstone was standing by just in case. She was very confident that the fire would be out Sunday just using ground tactics. That was the plan.

The fire as the firefighters arrive

I went to sleep in the back of the truck and watched the orange glow from the fire as night fell. Whenever I woke up during the night the orange glow was coming up from the site of the fire. It didn’t seem to get much bigger overnight.

Frontier Creek

Sunday morning I checked with Earl again about current information. At first the valley was full of smoke but it cleared off and the sun was shining. He said all the trails were still open and the word was still that they would be putting the fire out. I could see three green Forest Service trucks close to the campground entrance but no personnel. I told him in that case I’d be heading up Wiggins Fork to look for petrified wood. He asked me how far I’d be going and I said not far. I wanted him to know where I was.

I waded Frontier Creek and then hiked across the point on the trail by the cabin, then up Wiggins Fork, so I had pretty much gone around the fire completely. It showed as a column of smoke rising with the wind taking it slowly east. Couldn’t see any flames. Occasionally, as I was hunting the Wiggins gravel terraces for wood, I noticed that the column of smoke was getting bigger, but I assumed that was because the day was heating up.

Monday morning

Norton Point

Norton Point

About 10, I looked south down the canyon and the fire had spread down to the western banks of Wiggins Fork. Flames were twice as high as the trees. Some trees exploded from the heat, and I was close enough that I could feel the heat flashes on my face. I decided that was too close, so I walked north. The fire seemed to be burning faster right next to the bank than it was across the upper slopes. I didn’t want to head back down that way while the fire was burning so fiercely, since the wind then was stronger from the west, and flames were blowing east over the creek. I thought that if the fire jumped the creek I’d be in real trouble, and about noon they did. They spread north a lot faster on the east bank of Wiggins than on the west bank. Through the afternoon I kept moving north as the fire came north. I’d watch it from the terraces in the middle of the river. It was impressive. That whole end of the canyon looked completely cut off, and I didn’t see how I was going to get back to the campground. I figured they’d have to send a helicopter for me, and I was glad Earl knew where I was. I didn’t think climbing the ridge back over to the Frontier drainage would be a good idea. I could break an ankle or something, and that would put me in a place where nobody knew where I was. I knew I could stay out all night if need be—I had rain gear and matches (not that I needed matches) and I could build a campfire from driftwood to stay warm and use water from the creek to drink. I’d only been planning to stay out until noon, so I didn’t have much clean water and only a little food. I didn’t want to drink from the creek unless I had to.

By early afternoon a helicopter was cruising around overhead every so often, but way high, looking at the expanding fire, not low enough to spot me. But I still waved my hat and my handkerchief on a stick to try and get their attention.

Later Sunday morning

From Frontier Creek Looking at Norton Point

Late in the afternoon a fishing party from Nebraska of five men, four horses and a dog was coming south along Wiggins. They’d abandoned the Wiggins Trail because it was blocked by fire, and entered the streambed south of me. So I was behind them, but I waved my handkerchief on a stick and caught somebody’s attention, then I went down to talk with them. I had met them several days earlier. Like me, they’d heard that the fire was under control, small, and supposed to be put out on Sunday, so they went out fishing as usual.

Norton Point

Mark, the leader, said they were going to head south in the middle of the creek, stay away from any falling trees along the bank, and make for the camping area. I told them I wasn’t going to do that. No way. I had been caught in the woods during the 1988 fires in Yellowstone, with fires burning all around me in a 40 mph wind, and I knew fire could do anything once it got started. The end of the canyon was full of smoke, and fire was burning on both sides. I told them if they wanted to try that it was fine, and if they got through to let somebody know where I was.

They left, and as they disappeared into the smoke there were trees bursting into flame on the bank by them. A little later the helicopter came racing straight up the canyon, quite a bit lower this time. I thought they finally might be looking for me, and I found out later they were, so I waved like a crazy man, but they didn’t see me. I was right in the middle of the creek on a gravel terrace, in plain view. But they seemed to be going about 80 mph.

Monday morning -- one mile away

Then no more helicopter, and the fishermen had been gone for about 45 minutes, and the sun was heading behind the ridge, and I figured if I wanted to get back to my truck before dark I had to start south no matter what. It was cooling down and the fire was less severe by then. Smoke was still strong.

Norton Creek holding the fire from spreading west

So I headed into the fire area. Trees on the west side of the creek were bursting into flame every so often, and the fire on the other side seemed to be farther back in the trees but creating a lot of smoke. Some younger trees right next to the water and out on the terraces were fine, still green, but a lot of the driftwood on the gravel beds had burned and I was stepping over remnants of driftwood logs and trunks, smoking shadows of ash left on the rocks.

Trees Exploding

I found the place where the trail led around by the cabin—the way I’d come that morning—and it was burning, so I knew I’d have to go farther south. At one point I was wading across one of the streams and fell in, so that meant spending the night out wasn’t an option anymore. It was hard to keep my footing anytime I stepped in, and my ankles started swelling. My lips were sticking together and I figured that was dehydration. My legs were cramping, probably hypothermia. I kept telling myself, “Don’t do anything stupid.”

Monday afternoon from 30 miles away

Trees Exploding

I got down across from the meadow south of the campground, picking my way carefully through the braided streams to avoid the deepest parts, but it was dusk by then and hard to tell the depth of the water. I left the wood and my backpack on the east bank, and figured I’d come back for them in the morning. When I reached shore I needed to get moving as fast as I could to my truck and get into some warm clothes. It was probably about half a mile. I stopped on the way to let Earl and the Nebraska fishermen know I was okay. It was dark when I reached the truck, so I changed as fast as I could, but my hands weren’t working right. I couldn’t tie my shoelaces, and my legs were still cramping, and my teeth were chattering. I had a quart of sun tea that was still warm from the day’s heat, so I drank all of that. I started the engine and sat in the cab until it got warm, but I didn’t feel any warmer. I wanted to get a fire started in my little camp stove and boil some water for tea, but I couldn’t use my hands for anything. With my coffee cup and a teabag I went miserably back across the meadow to the Nebraska fishermen to see if they could boil some water for me, and they invited me to stay for supper. I could barely talk. They had fresh elk ribs and chicken and corn on the cob. I couldn’t hold the corn on the cob in my hand. Finally I could feel my hands again and I had some food in me, so I felt pretty good, but I was exhausted and I kept staring off into space, picturing the scenes of that afternoon with the fires coming up the canyon toward me. We all sat around the campfire and watched the flames from the fire against the mountains, which by then was in the upper slopes on the east side of the valley. Nothing like a nice forest fire to pass the time.

Vapor cloud from fire on Caldwell Creek 8.11

Burnt area near Norton Creek 8.11

The next morning I made three trips back and forth to the place where I’d left my wood and gear. I didn’t want to risk falling in again. Getting in the water even for a minute left my legs cherry red. There was nothing much to do the rest of that day (Monday) except watch the fire, since all the trails but Frontier Creek were closed, so I said goodbye to the fishermen and got some advice from Earl on other places south along the river to look for wood, and that’s where I headed. The fire was just starting to spread north along Frontier Creek, so that meant it would eventually jump the creek and spread along the western side, where the campground was. The firefighters were trying to save the cabin and the campground, but otherwise letting the fire go. The Nebraska folks were hoping to stay, but I figured Frontier would be closed soon (and it was). They had plans to be at Double Cabin a week and didn’t have any other options set up. Depending on the wind, you were either getting a wonderful view of the huge column of smoke and trees bursting into orange flame, or you were in the middle of the smoke with watering eyes.

Caldwell Creek on the other side of the mountain

When the Forest Service decided to “let the fire burn,” I don’t know if that was just another way of saying they had lost control of it. Not that it made much difference at that point. One person who saw the firefighters come on Sunday morning said they didn’t seem to be in any rush. They were having coffee, chatting, not dashing over to the fire. I guess they were real confident they could put it out.

Caldwell Creek

Of course, they were telling everybody, “We’re putting it out and all the trails are open,” so they knew there were people on the trails. I wish they had sent somebody out on a horse to let me know. Earl knew right where I was and he told them. I wasn’t much more than a mile away at that point.

I haven’t heard of anybody getting injured by the fire, but I was pretty banged up and exhausted. At home in Indiana I finally got all the smoke smell washed out of my truck. I hear the campground is open again. I may go back next year just to see what it looks like. The last time I was there in 1992 all the trees were alive, so it looked a lot different when I got there this year, and next year will be something else again.

-Tom

View up Caldwell Creek from road 6 miles to the south 8.11

A Forest Service map of the fire

Roads: Going Over the Edge

Friday, September 2, 2011

The rock ridge that extends out towards the Owyhee River from the Jake’s Place mine becomes a vertical cliff before it meets the talus rock slope below. This is the first place that I could move the route of the road out of this canyon and onto the rock slide between this canyon and the next. After the nine switchbacks down the canyon, the road had to go past the base of the cliff, across the rock slide between the two canyons, and down into the next canyon. The area that contains the best jasper on the Christine Marie Claim is in the slide between the next canyon and the one after that -- on the southern portion of the claim.

I had just finished building switchback number nine and was looking down towards the cliff that I had to go around. It looked like I had one more, steep slope down. Then I could lessen the slope of the road and even build it level to the horizon for a while. The rest of the road would be a downhill route around the sides of hills to the south end of the Christine Marie. There would be no more switchbacks.

I was having a lot of trouble building the road around the corner at the bottom of the cliff. There was not a lot of rock to work with and not much room to move it either. I had to angle the road down again to get past the lower end of the loose rock slide created from the mining above. I was in a bunch of big rocks when I got stuck with the dozer almost sideways on the road. I could not move backwards and the only way forward was down over the slide and down the slope.

Rationalizations for actions in dangerous situations are easily colored by desires that do not reflect reality. I remember thinking that I could just drive the dozer down the slope and start working on the road from the other direction. Never mind that ten tons of steel goes down a slope with a great deal of speed, that the machine could roll over easily killing me in the process, or that operating the dozer on a 60 degree slope might be a little different than operating on flat ground. But the road had to be built.

I went over the side. I lost all control. I grabbed the right clutch to straighten the machine out as I felt it slide and immediately grabbed the left clutch as I started to slide the other way. With my right hand free I slammed the hydraulic control forward lowering the blade. Rock collected in front of the blade and stopped the machine upright facing straight down the hill. The ride lasted about four seconds.

I sat down on a rock for about 10 minutes with my whole body shaking. I had survived the catastrophe which resulted from a very rash decision.

I walked up to where Jake was working and told him what had happened. The next day he brought his front-end loader down, continued construction on the road down past where I went over to the side and built a spur road over to, and just under, my dozer. I started the dozer, drove it onto the spur road and up to the main road. Getting back on the machine was one of the hardest things I have ever done.

Christine Marie: My First Jasper

Friday, September 16, 2011

My First Christine Marie Morrisonite Specimen

I had a productive day working on the road with the dozer, and I was getting close to starting the last downhill stretch of the road. I walked the road back up to the cabins and made supper – a ½ mile and 600 foot climb. I was full of anticipation that I soon would be mining jasper. This was the middle of June, and the days were long. I walked over to Jake’s cabin told to him that I thought I would walk back down and inspect the area I intended to mine. I walked down the south canyon. This canyon contains the rock formation known as the pinnacle which is in the center of the Amy Ellen Claim above the south end of the Christine Marie Claim. The descent is steep from the top of the canyon, but it is a shorter distance than walking down the road, and there is a good game trail to follow.

The pinnacle (right) is on the opposite side of the photo from the Christine Marie mine (left).

The area which had signs of good jasper is a strange mixture of very large rocks (5-10 tons each) and small shattered rocks (1/2-2lbs.). I could see that it would be necessary to route the road underneath the largest rock on the side of the hill. I would probably start working under the big rock. I saw a small piece of jasper sticking out of the ground. I picked it up and wiped off the dirt. The piece was loose and not attached to any larger rocks. It was part of a seam with a very dark blue – almost black – outside and a soft looking light blue “egg pattern” on the inside. It had a gemmy consistency and a beautiful pattern. I immediately started back up the canyon to show Jake.

The Pinnacle above the Christine Marie Claim.

After the steep climb out of the canyon, Jake and I sat in his cabin examining the rock. “You know,” Jake said, “there are two good sides to that rock, and there should be two more pieces of that seam down there.” And then, to my surprise, he said, “Let’s go down and take a look.” For the third time that day, down the canyon we went with about two hours of light left in the sky. I had not marked the spot where I found the jasper, but I felt sure I could get right back to that spot.

We walked all over the side of the hill, but could not find another piece of jasper like the one I found earlier. We climbed back up to the cabins and arrived with just a glow left in the western sky. In the next eight years of mining this area, I never found another piece of this vein.

The Christine Marie Mine at its most dug.

Mining the Christine Marie: My Second Machine

Friday, September 30, 2011

My friend Jake leased on the “Big Hole” claim from Lissa Caldwell. She was the wife of Tom Caldwell who worked the claim in the middle 1970s. Tom owned the claim, and Lissa inherited it when he died. It was originally purchased by Tom’s father and given to Tom as encouragement for his mining activities. Tom was known as a very good agate miner and was hired by other claim owners to work their claims.

Before Tom Caldwell decided to try mining Morrisonite, most of the mining had been done by hand. The lay of the deposit on the Big Hole Claim – later renamed “Jake’s Place” – on the precarious hillside was pretty well known because of all the previous hand work. Tom decided to ask Jake to help him get started and open up the deposit so that it could be mined more efficiently. Tom owned a CAT 955 track frontend loader, and Jake owned a Case 850 frontend loader. They moved both machines, a compressor, drill, and explosives out to the saddle above the deposit and set to work. They built the two still existing cabins in 1976 on the saddle so they would be safe from vicious weather which came across the ridge.

Jake and Tom drilled 12 foot holes with Tom’s 80 pound hand-held sinker drill, filled the holes with explosives, and broke up the rock. They then used both frontend loaders to push the barren rock over the edge as they worked down the side of the steep hill towards the deposit. They did this over and over for about three weeks without getting any jasper. About this time Jake moved back to mine Bruneau where he knew he could produce rock he could sell easily.

The area that Tom and Jake exposed is known as the “South Pit.” This area produced some very fine jasper. Some pieces from this area have gone to the grave with their owners at their request. A piece from the South Pit, now in a private collection, was featured in our 2008 Calendar of Fine Agates & Jaspers during the month of October. Most of the jasper in the Morrisonite area is found in shattered or cracked rock, in or under steep rock slides. One time Tom was working in the South Pit with his 980 frontend loader, and a rock slide buried his machine with him in it. He dug himself and his machine out by hand and got his machine up 600 feet, back on the saddle. Tom did not mine much Morrisonite after that.

The South Pit is now buried under about 20 feet of overburden which was mined from the North Pit on the Big Hole/ Jake's Place Claim and Veronica Lee Claim in the late 1980s and early 1990s. Tom’s drill was found years later rusted and frozen up. It was put in a container with oil for a year in an attempt to salvage it. After it was working again, I took it to Mexico where it has become responsible for most of the Coyamito Agate in the market today – there is not a deposit on the Coyamito ranch that does not have holes made by this drill.

Tom’s frontend loader ended up in Herrington’s Rock Shop in Adrian, Oregon. Jake obtained the machine with a lease, performed some repairs on it, and moved it back to Morrisonite in 1986. Jake sold his Case 850 to Glenn Pegrem who used it on some of his claims north of Jordan Valley about 35 miles from the Morrisonite claims.

Jake watched me build the road to the Christine Marie for two years with my ancient D4 Dozer. He told me that I needed a better machine and said he knew where I could get one that would not cost too much. He introduced me to Glenn, and, one year and $8,000 later, I had a Case 850 frontend loader – my second machine. I returned it to the Morrisonite area, and it stayed there for eight years.

Mining Morrisonite: Christine Marie – CASE 850

Friday, October 14, 2011

The levers.

Operating a CASE 850 frontend loader is about as different from operating an old D-4 Dozer as it gets. While operating the dozer, I was constantly moving my arms, pulling levers to steer the machine. The CASE could be driven with just my left hand! There were three little levers right next to each other on a pedestal between my legs as I sat on the machine. The right lever, which can be moved with one finger, provides power to the right track in low gear if pulled back and high gear if pushed forward. The left lever does the same for the left track. The middle lever moves the machine forward if pushed forward and backward if pulled back. The middle position for each lever is neutral.

Gene and the CASE-850 hard at work.

The machine can be turned to the right two different ways. By placing the left track in high gear and the right track in low gear, the left track will move forward faster than the right track turning the machine to the right. This is an advantage for the CASE because most other machines turn by subtracting (breaking) power to one track or the other rather than having power to both tracks. The CASE can also be turned to the right by putting the left track in high or low and leaving the right track in neutral. The weight of the machine will hold the right track in place while the left track drives forward, turning the machine to the right.

Gene, the happy miner.

Because the CASE 850 has a torque converter transmission, the tracks are free to roll if there is no power directed to them. But if turning right on a steep hill by providing power to the left track and leaving the right track in neutral, the machine can actually turn to the left instead. The free-wheeling right track can outrun the powered left track and move the machine to the left rather than right. This can make for some interesting times while operating on steep ground. Also it is very important not to allow the engine to stall; this will result in a 10 ton machine rolling down a hill with nothing to stop it but the bottom of a steep ravine.

The CASE 850 does have breaks, but they are a joke. They were designed using old car parts and never worked well. I almost never used them. If I was driving the machine forward and needed to stop it, I could easily put the machine in reverse and accelerate. This machine had a foot-operated accelerator just like a car. The automatic transmission or torque converter would slow the machine to a stop and start moving backward.

A view of the levers from the seat.

Mining the Christine Marie: Abrasive Rock

Friday, October 28, 2011

The two host rocks separate.

The jasper on the Christine Marie claim is in a steep rock slope about halfway down the canyon from the rim above. The host rock is labeled a welded tuff, and extends from the slope of the hill up past the cliff above to the pinnacle on the Amy Ellen claim; a distance of around 200 yards. The jasper formed in cracks in the tuff before it was in its present position. The entire hillside is a mixture of very large rocks (2-10 tons) and millions of small ones (1/2-5 pounds).

This rock is very abrasive. Because of the rock’s abrasiveness the rocks do not fall easily, but cling to each other. This quality contributes to the steepness of the area by not allowing rocks to erode downhill as fast. To illustrate this, it is possible to take two flat pieces of this welded tuff, place one on top of the other and tilt the pair of rocks almost 80 degrees before the top rock will fall off. Try this with most other rocks and the top rock will start to slide off with a tilt of a little over 45 degree

Gene holding the two pieces of abrasive rock.

The jasper in this deposit is scarce, but very good. A lot of rock must be carefully moved to collect a small amount of jasper. The abrasiveness of the rock takes a toll on your gear, as well. There were many days where a new pair of gloves in the morning would have one or two holes in the fingers by late afternoon. Using duct tape on your fingers was a common practice used to get more use out of a pair of gloves, or a little less wear on your fingers. I learned to buy a new pair of boots before I came out to the mine because a pair of boots lasts about a month working in this rock. I always use steel toed boots to protect my feet. After a month of mining Morrisonite, the leather would be worn off the toes of the boots revealing the scratched, shiny metal underneath.

Notice how tilted the rocks are, and they still stay together.